District 4 Sen. Billy Hickman, R-Statesboro, goes back to the Georgia General Assembly this week with a boxful of education proposals addressing topics such as keeping students' phones out of classrooms, countering chronic absenteeism, making kindergarten actually compulsory and bringing retired teachers back to work.

While continuing his long career with the Statesboro accounting firm that is now Dabbs, Hickman, Hill & Cannon, he was first elected to the state Senate in 2020 and is heading into his sixth year as a lawmaker. Hickman now chairs the Senate's Education and Youth Committee and is vice chair of the Higher Education Committee, secretary of the Finance Committee and, as a member of the Appropriations Committee, leads its education subcommittee.

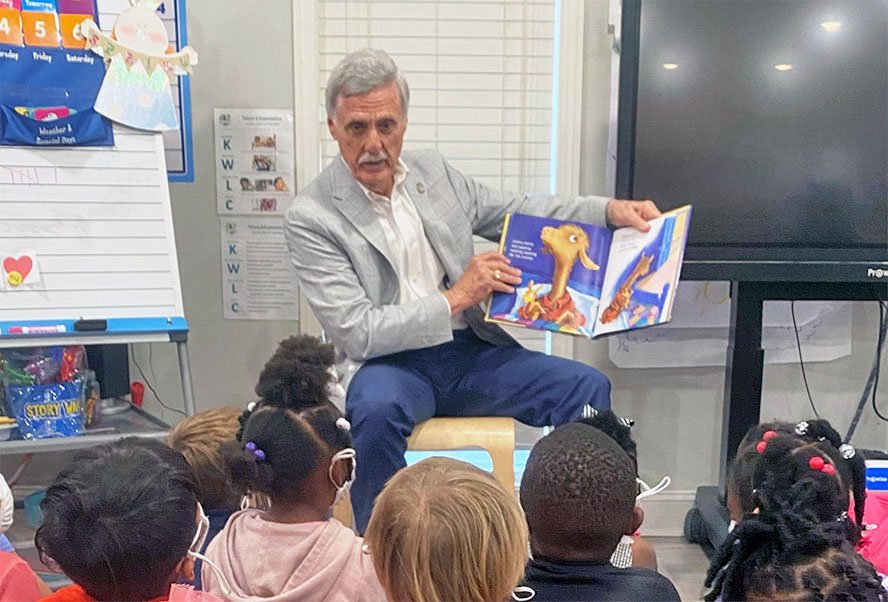

"As you well know, I'm a CPA, but literacy has become a priority for me in the Senate," he said.

Three years ago, Hickman sponsored Senate Bill 211, which created the Georgia Council on Literacy, made up of 10 legislators and 20 other citizens, and then was appointed to that council by Lt. Gov. Burt Jones.

For the interview on his outlook for the 2026 legislative session, which will convene Monday, Hickman brought out a literal cardboard box full of things he said he's been working on since last summer. From a folder full of the education-related materials, he supplied a copy of a one-page summary of three central points. The first of these was about the specific literacy initiatives.

"We are just getting started," Hickman said. "Georgia has made significant strides in improving literacy, but our work is far from complete. The Senate remains committed to providing strong oversight and ensuring accountability until every child in our state can read proficiently."

In 2026, he said, the state Senate's focus should be to monitor key, already established literacy initiatives closely to "ensure that all barriers to reading success are addressed."

Class phone ban

But Hickman also talked about several pieces of new or pending legislation that might also be said to target "literacy" in a more general sense by tightening expectations for students in grades K–12.

A bill to keep personal cellphones and similar electronic devices out of students' hands while in kindergarten through eighth-grade classrooms passed in 2025 and was signed into law by Gov. Brian Kemp last May. The Bulloch County Board of Education now has a policy in place, and all school districts are required to have one by July 2026.

Now, the Senate has a bill drafted to expand this restriction to high schools, grades 9–12, essentially prohibiting students from having "a cellphone or any other type of electronic device other than (what) has been issued by the school," Hickman said.

In earlier years, suggestions of a ban of this type drew pushback from parents who insisted the phones provide needed emergency communications between students and families. But the perception of some officials at the state and local levels changed after the deadly September 2024 shooting at Apalachee High School near Winder. One concern is that the volume of such calls can interfere with communications among first-responders, Hickman said.

However, the nickname of last year's legislation for grades K–8, the "Distraction Free Act," emphasized another motivation for the change. Hickman referred to a report by an Atlanta news site that after one teacher asked students to help keep track, their phones, all together, registered calls or dinged with messages more than 250 times during a single class period.

"So, I think with the fact we've drawn so much attention to this, people are really realizing there is a hindrance to learning," he said.

Requiring kindergarten

Another Georgia Senate bill that has already been drafted is meant to "make kindergarten mandatory," as Hickman put it. As he acknowledges, many people thought Georgia already had kindergarten as a compulsory grade, but it turns out that whether attendance was actually required or not depended on a child's birthdate.

At this point, Georgia's mandatory attendance law requires children to be enrolled in public school, private school or home schooling between their sixth and 16th birthdays.

"Right now, the age range is 6 to 16, and we're going to drop the age to 5," Hickman said. "The Senate bill was drafted, and we're waiting on the fiscal note — the cost of it."

When a similar bill was prepared about two years ago, the fiscal report arrived too late for the bill to move forward. At that time, about 8,000 children "in Georgia that qualified for kindergarten were not in kindergarten each year," he said.

Those were children who turned 6 at some point during the year, but were still 5 when kindergarten classes started in August and were never enrolled, he explained.

"If your birthday is July and my birthday's September and your parents send you to kindergarten and mine do not, when you go into first grade, you know your numbers, you know your colors, you know how to sit still, you know how to line up, all those things that I don't know, so I'm basically a year behind you," Hickman said.

A relatively small portion of parents have kept children out of school because of this age gap, since around 130,000 Georgia children turn 6 each year, according to census numbers.

"So, can we afford for those few to be left behind? I don't think we can," he said. "If we really want a truly literate work force, we can't afford for anybody to be left behind.'

Chronic absenteeism

A Senate study committee that met last summer examined the problem of chronic absenteeism in schools.

"That's an issue, because if a kid is not in the classroom, they can't learn," Hickman said.

"Chronic absenteeism" is defined as when a student misses 10% or more of class days, or 18 days out of Georgia's standard 180-day school year.

"If a kid misses one day, the studies show that it takes 1.9 days for them to catch up," Hickman said. "Our chronic absenteeism in Bulloch County is almost 20 percent. One in five kids in Bulloch County is chronically absent. We've got several of our schools that are above 25%. So, we have got to address absenteeism in these schools, we've got to figure it out, and it's across-the-board."

He said "almost 20%" for the Bulloch County Schools' absenteeism, but that may reflect some recent improvement. In data he quoted from the study, Bulloch County's chronic absenteeism rate was 22.9% in the 2023–24 school year. Statesboro High School's rate was then 27.7% and William James Middle School's, 28.6%. Also that year, chronic absenteeism rates were 27% in the Savannah-Chatham County Schools and 24.6% in the Evans County Schools in Claxton.

"A lot of this came about because of the COVID situation," Hickman said. "In all of Georgia, 21.7% of kids are chronically absent — over 370,000 kids a year. So, we as a Senate and a House have got to address chronic absentees."

Teacher shortage

"One thing that I worked on real hard last summer … we've got a huge teacher shortage in Georgia," he continued. "In December of 2024, there were 5,300 vacancies in Georgia for teachers."

Through a resolution, he called on Jody Barrow, executive secretary of the Georgia Professional Standards Commission, which oversees teacher certification, to assemble experts and educators "to tell us why people are not wanting to go into education, and why people are getting out of teaching," Hickman said.

Many teachers are dropping out of teaching after only five years, according to information he has collected, and the typical retirement age is 25 years.

"Our starting teachers' salaries are so low," Hickman said. "Now, some school systems bump them up more than this, but the baseline is $43,000 to $44,000 a year. … We've got to look very seriously at our beginning teachers' salaries. We're doing a great job with our average teacher salaries; we've got that up to where it needs to be."

He said he has a meeting at the Governor's Office about beginning teachers' salaries on Thursday.

Returning retired teachers

Meanwhile, as a stopgap measure, Hickman supports expanding "retired teacher return-to-work legislation" through Senate Bill 150.

Currently, those who retire under Georgia's Teacher Retirement System can return to work as educators for 49% of the full-time monthly salary, in effect limiting them to half-time work.

"We've got a lot of teachers that are retiring at 50 years old, and what are they going to do the rest of their lives?" he said.

Previous legislation that would expire in December 2026 allows retired teachers to return to work full-time in underperforming schools, which Hickman said is limited to those schools ranked in the bottom 25% by state performance standards.

"My bill would allow a teacher to come back after they've retired with 25 years," Hickman said. "They've got to stay out a year from teaching, but they can come back and teach English-language arts, science, social studies, special education, math or CTAE (Career, Technical and Agricultural Education)," Hickman said. "My bill will allow them to teach anywhere in Georgia."

His proposal, as drafted, would sunset in 2034, by which time he hopes the state will have found a longer-term solution to the teacher shortage, he said.