Statesboro City Council by a 4-0 vote Tuesday evening granted the Statesboro-Bulloch Remembrance Coalition permission to erect a historical marker next to City Hall memorializing the known nine known victims of lynching in Bulloch County.

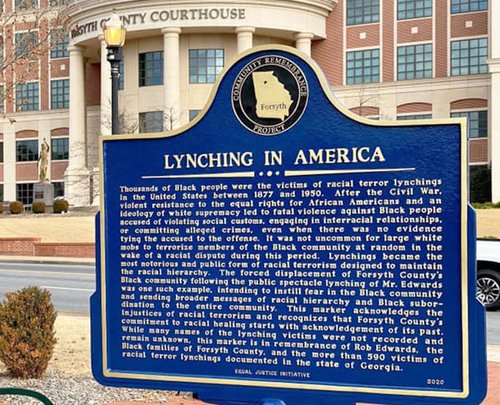

Organized in 2019, the local Remembrance Coalition is working with the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit organization based in Montgomery, Alabama, to create and place the marker here as part of EJI’s national Community Remembrance Project. EJI, working with local remembrance coalitions, has installed markers documenting lynchings in 23 states from coast to coast, according to information on the organization’s website. In Georgia, EJI as partnered with county coalitions to install lynching memorial markers in six counties so far: DeKalb, Forsyth, Fulton, Gwinnett, Troup and Walker.

So the one now expected to be installed later this year off the eastern end of Statesboro City Hall’s front porch could be the seventh in Georgia and the first in the southern part of the state.

“The Remembrance Project is dedicated to creating opportunities to make space for necessary conversations that advance truth, healing and justice around racial terror, violence and most importantly, its legacy,” said Adrianne McCollar, one of the co-chairs of the Statesboro-Bulloch Remembrance Coalition.

McCollar, who is Mayor Jonathan McCollar’s wife, and the other co-chair, Dr. Patrick Novotny, a Georgia Southern political science professor, spoke to the mayor and council during their 3:30 p.m. Tuesday work session. Later during the 5:30 p.m. regular meeting, the council voted approval of an easement allowing the coalition to maintain the marker on city property and promising that the marker will not be moved or altered without the coalition’s consent.

“We want to invite others to the work, to influence the coalition projects, and we believe in our collective community power to resurrect truth and confront the hard past in an effort to build a brighter future,” Ms. McCollar said.

The Equal Justice Initiative has documented lynchings of about 4,442 Black people that occurred in the United States between about 1882 to 1968. A “widely supported campaign” with goals of enforcing racial subordination and later, segregation, lynching spurred the Great Migration of African Americans from the South to the North and Midwest, she said.

Lynching in Bulloch

The lynching, by burning at stake, of two Black men in Bulloch County, Will Cato and Paul Reed, on Aug. 16, 1904, became infamous even in a time when racial violence was occurring in many states. The lynchings here were widely reported in newspapers along with details of the Hodges family murders of which Cato and Reed were convicted by an all-white jury.

But they were just two of the nine local victims of lynchings from 1886 to 1911 confirmed by EJI researchers. Most of the others were never convicted or formally accused of anything before being killed in brutal ways by groups of white people, as McCollar illustrated by focusing on the lynching in late August 1904 of Sebastian McBride, whose home was near Portal.

“Mr. McBride was a Bulloch County man. He had no association with any alleged assaults, as was frequently the excuse for lynchings,” she said. “He was dragged from his home and he was beaten to death.”

McCollar held up, and distributed to the council, printout copies of the front page of the Aug. 30, 1904, Savannah Morning News.

As she noted, the story about McBride’s death states that he was taken out of his house “by a mob of five men,” carried to the woods, “whipped severely, and then shot.” He lived long enough to say the names of three of his alleged assailants to other people, who reported them to a coroner’s jury.

“So this happened … about 10 days after the Cato and Reed lynchings, so August of 1904, this was a month of just terror,” McCollar said.

Tale of 2 markers

Assistant City Manager Jason Boyles, in a memo about the location for the lynching memorial marker, noted that a spot near the sidewalk on the east side of City Hall had been suggested, “since there is another historical marker on the west side of City Hall.” He said he agreed this would be a suitable location.

The existing historical marker by the west end of City Hall’s front porch memorializes an event of a very different character. Furnished by the Bulloch County Historical Society, the “Fabulous Fifty of 1906” marker recalls the Statesboro-Savannah round trip of Dec. 1-2, 1906, by a delegation who made a successful effort to bring the First District Agricultural and Mechanical School to Bulloch County. First District A&M grew and evolved over decades to become Georgia Southern University. Relocated in 2020, that marker appears in view of the Fabulous Fifty mural the Historical Society had professional artists paint on the east-facing wall of a neighboring building.

McCollar, in her comments Tuesday, suggested a link between the terrible events of 1904 and the quest for a college in 1906. Before the racial violence of 1904, Statesboro had become a bustling small town, a center for the turpentine industry, moving forward with new inventions such as electric power, she said.

But the summer 1904 lynchings brought disapproval from far and near.

“People started to lose businesses after that,” she said. “It was frowned upon, what had happened here, and so these Fabulous 50, probably in connection with many other things, but in an effort to turn the page from what Statesboro and Bulloch County had become known as, said … let us be known for something else.

“So to have this marker on the other side of that, it broadens the conversation,” she said.

Novotny, in his comments, further linked the proposed marker, and the 1906 marker, to City Hall’s current location in the historic Jaeckel Hotel, which he noted opened in 1905. (This corrected a misstatement in the coalition’s request letter that journalists had stayed there while reporting on the 1904 violence.)

The placement, he said, would represent “an arc of progress for our city.”

“Statesboro City Hall welcomes newcomers every day to our downtown and to our city, and I think thanks to this marker and to the other, everyone, especially newcomers and visitors, will now be able to learn parts of a painful past, but also learn about a progressive past, present and future of commerce and education,” Novotny said.

One speaker against

During the public comments time after the start of the regular council meeting, one local man spoke in vehement opposition to the lynching marker. Jeffrey Marshall Webster, who administers a “White Heritage” social media group, called supporters of the marker project “race hustlers.”

“Council members and friends and neighbors, I ask you to reject the placement of the lynching memorial marker on city property,” Webster began. “This proposed marker is just another blatant attempt on the part of professional race hustlers to stir up racial animus and further their own political ends, enhance their reputations and line their pockets.”

But another white man, Matt Gerig, who spoke next, was a new Statesboro-Bulloch Remembrance Coalition member. He said, “The need to confront Statesboro’s history of racial inequality is more urgent than ever.”

The group and its supporters are diverse, as seen when about 100 people attended the coalition’s first publicized event in early January. Upwards of 15 coalition members attended Tuesday’s meeting, many of them standing in a show of support.

Council members had received a lengthy “draft” of the marker text. But it was a very rough draft and considerably longer than will fit on the one side of the marker provided for information about local lynchings, coalition members said. The other side will contain EJI’s text about lynchings nationally and in Georgia.

“What we gave council is exhaustive. It gives the spirit and the story that we would like to convey, but it will have to be ultimately vetted through EJI,” McCollar said.

Now that the location has been approved, that process will begin and is expected to take at least three months, she said.