While highlighting the Willow Hill Heritage & Renaissance Center as “more than a museum,” during last weekend’s annual festival, the center’s leaders nevertheless emphasized the site’s authentic history – including heroism in overcoming setbacks and even terrorism.

Another topic was how families, churches and community organizations can document their own triumphs, tragedies, and the identities and relationships of individuals through “community archiving.”

Founded in 1874, nine years after the Civil War ended, by formerly enslaved people who valued education for their children, the Willow Hill School near Portal, Georgia, saw one of its early leaders, Isaac Riggs, terrorized and beaten by several white men in 1876. Seventy years later, in 1946, when efforts were underway for African Americans to vote in Bulloch County for the first time in half a century, the Ku Klux Klan burned a cross on the school grounds.

The Willow Hill center’s board president, Dr. Alvin Jackson, his daughter Dr. Nkenge Jackson-Flowers and Lawrence Heber, a Georgia Southern University graduate student completing his master’s degree in public history, presented the featured lecture, “The Heroism of the Black Men of the Willow Hill Community during the 1946 Gubernatorial Election,” Saturday afternoon. The presentation was first developed for the Association of African American Museums conference and in honor of the 60th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

“We’re going to talk about a little-known story that reflects on our community here at Willow Hill in 1946,” Jackson began.

He assumed for a moment some historical background knowledge on the part of listeners. For example, in the Reconstruction era that followed the end of the Civil War in 1865, and with the adoption of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1868 and the 15th Amendment in 1870, African American men did receive and exercise the right to vote even in the Deep South, and a number of black men were elected to state legislatures and some city and county offices.

“Now, most of you know that is 1896 there was a United States Supreme Court decision, Plessy versus Ferguson, which established ‘separate but equal,’” said Jackson. “During that time period, many of the gains that had happened after slavery and before the rise of Jim Crow, African Americans would lose many of their opportunities.”

Freedoms lost & rewon

“They were voting and doing many other things, but with the separate but equal doctrine, many of these were lost. There were a lot of lynchings and other sorts of things that were happening.”

“And then in 1946 and in the ’40s there were Supreme Court decisions that were going to allow African Americans to vote again, and the KKK came to this very campus, right next door, to intimidate African Americans not to go to the polls and vote.”

Later, showing historic photographs of the Willow Hill School and its families projected on a screen, Jackson announced one of the saddest pictures.

“This is the cross that was burned at Willow Hill in March of 1946,” he said. “Mr. Roosevelt Campbell, who was principal one at Willow Hill, took this photograph and preserved for the ages the thoughts and ideas that this photograph carried, burning a cross to prevent African Americans from going to the polls to exercise their right.”

Voter suppression

Heber, who has worked on various projects with the Willow Hill Center as an intern there – then placed the 1946 events in the context of “a brief history of voter suppression.”

In fact, in the early Reconstruction period of the late 1860s, Georgia’s government of openly white-supremacist Democrats had opposed having African Americans participate in elections, refusing to ratify the 14th Amendment and instead enacting “black codes” to maintain inequality.

So the U.S. Congress passed the Reconstruction Act, placing Georgia back under military control, with a military government.

With over 100,000 black men registered to vote, 25 black representatives and three black senators were elected to the Georgia Legislature.

“Almost immediately in the first meeting of the state Legislature, the Democratic members of the House schemed with white Republicans to kick out every black member of the state legislature,” Heber said.

Military control was exerted a third time and the state Constitution rewritten more than once before Georgia was formally readmitted to the Union. But efforts to disenfranchise black men – women of all races had yet to attain the right to vote – continued and intensified.

In addition to giving a count of terrorist actions such as murders spearheaded by the Ku Klux Klan, Heber described Georgia’s use of legislation, such as expansion of the list of crimes for which convictions could bar people from voting.

“By 1890, very few African Americans were able to participate in the election,” he said

That same year, the state Legislature forced all political parties to use “white primaries,” effectively blocking further African American participation in Georgia elections.

More than half a century later, in 1944, the U.S. Supreme Court in Smith v. Allwright declared Texas’ all-white primary system unconstitutional, and in a 1946 decision, this was extended to Georgia’s Democratic Party “white primary.”

That made the 1946 election a momentous one, in which incumbent Gov. Eugene Talmadge “reoriented his entire campaign on the promise of doing everything in his power to stop African Americans in Georgia from exercising the right to vote,” Heber said.

The tactics of the Talmadge campaign included fabrication of votes in some counties – documented by the FBI but never prosecuted – and bankrolling the use of a state law that allowed any voter to challenge another voter’s registration. That led to the purge of an estimated 25,000 votes just before the July 17 three-candidate Democratic primary, Heber noted.

Meanwhile, registration drives resulted in nearly 140,000 African Americans being prepared to vote.

Talmadge lost the popular vote to James V. Carmichael but won the “county unit” vote, a system, similar to the national Electoral College, used in Georgia elections until it was ruled unconstitutional 17 years later. Already ill, Talmadge died in December 1946, leading to the “Three Governors Controversy,” which would require a separate story.

The cross burning

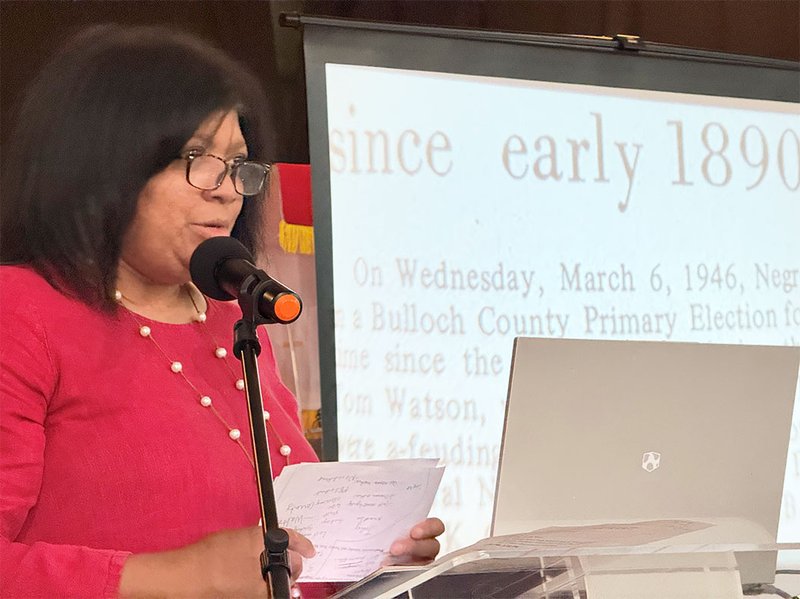

Jackson-Flowers picked up the thread of the March 1946 cross burning by summarizing her father’s 1994 recorded interview of the late John W. Lawton, vocational agriculture teacher at Willow Hill School in the 1940s and later its principal. Lawton, who lived to be over 100, said the meeting he was attending at the school that night was one of his classes with farmers.

“He said about 30 cars showed up, with their lights on,” she summarized. “They burned their cross, to intimidate. He said they weren’t intimidated, and they went to vote.”

That was just before the local March 1946 election, reported in a local newspaper back then as the first time African Americans had voted in Bulloch County in 50 years.

But while the FBI documented voter suppression incidents in other Georgia counties, a brief note in an FBI report at the time said there had been none in Bulloch.

“So we are able through these oral archives to present a different narrative,” Jackson-Flowers said, “and I think it’s important for all of us to know what really happened so we can encourage our future generations to understand how important, and how hard fought, the right to vote was in this community and in other communities.”

Following that lecture presentation, a different panel consisting of Ronald W. Bailey, Ph.D., professor emeritus of African-American studies at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champlain, and LaPortia Mosley, from the Georgia Historical Society’s archives at its Savannah Headquarters, spoke on “community archiving.”

‘Elephant in the room’

At one point Jackson-Flowers asked the panelists to talk about the biggest challenges they see to community archiving, preserving stories and documents of “lived history,” from local people and organizations.

“I’ve got say this because the elephant in the room is, as we sit here talking about the importance of this work, other people are talking about erasure,” said Bailey, who is originally from Claxton and now lives in Savannah.

“So, the biggest challenge is getting a broader societal agreement that people’s diverse histories (are worth preserving), he said, “because we all didn’t come over here, only a few people came over on the Mayflower.”

He said he would have to check how many people actually came over on the Mayflower, but thinks “a whole lot more came over on slave ships.”

“And I’ll use that comparison to encourage us not to think so narrowly about preserving the broadest scope and sweep of American history, and the diverse experiences,” Bailey said.