For the 150th anniversary of the original Willow Hill School and community, the Willow Hill Heritage & Renaissance Center held a symposium Saturday morning that focused on the sacrifices of African American soldiers — and also sailors, marines and others from Bulloch County who served in the military — and efforts to correct for a dearth of information and pictures by collecting what is available.

Saturday's symposium and a Gospel Fest on Sunday evening constituted this year's Willow Hill Heritage Festival, held as usual on Labor Day weekend. In addition to the historic school's 150th, the center marked the 60th anniversary of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, particularly with the Gospel Fest's headline performance by Rutha Mae Harris, now 83, one of the original Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) Freedom Singers.

One of Saturday's presenters, Brian K. Feltman, Ph.D., professor of history at Georgia Southern University, started working with students last semester on a project to document all of the soldiers from Bulloch County known to have died in World War I in a digital exhibit. But the students found that much more information, including photographs, was available for the white soldiers than for the black soldiers.

"What we found when we started this project — and I did this with my World War I class, so I have to give my undergraduate students a lot of credit for the research — was that the American Legion, and then especially the American Legion Auxiliary, which was the women's branch, they did a really good job of collecting information about the fallen white soldiers, but the Legion of course would have been segregated, there would have been no black members at that time, and so there is very, very little on the black fallen soldiers."

Both the American Legion, and its Auxiliary, which was originally for wives, mothers and other female relatives of veterans, were officially founded in 1919, just after the war.

Work to build the digital exhibit, the Bulloch County World War I Memorial Project, continues. Feltman's email address for those with information or artifacts is Bfeltman@georgiasouthern.edu.

World War I project

Feltman's students set out to create biographies of all 26 soldiers from Bulloch County who died in World War I, which lasted from July 1914 until November 1918, with the United States involved from only April 1917 until the end.

"Of the white soldiers we've got photographs, we know where their graves are located, we've got letters in some cases, but with the black soldiers we have very, very little," he said. "So one of the things I hope that we can do is find the descendants who say, 'Oh, I've got a photograph of that guy. That was my great, great uncle,' or whatever the case may be."

Of those 26 fallen soldiers from Bulloch, exactly 50%, or 13, were African American and 13 were white. But only two of the black soldiers' deaths occurred from battlefield wounds, while the other 11 died from disease, mainly in the "Spanish flu" pandemic that began in 1918, he said.

"The number of battlefield fatalities is higher for whites because, of course, most African Americans were not given the opportunity to serve in the front lines," said Feltman. "There were what was referred to as stevedores, doing loading and unloading, logistical kind of work."

Some of the deaths from illness were recorded as from "bronchial pneumonia" or other lung diseases related to the flu outbreak, as well as some directly attributed to influenza, he noted. As previously reported from a Bulloch County Historical Society program, four of Bulloch County's World War I fallen soldiers were victims of the October 1918 wreck of the troop ship HMS Otranto, but those four were white.

World War II project

Georgia Southern public history graduate student Lawrence Heber, who has been interning with the Willow Hill Center since his undergraduate years, asked for assistance from the community with a similar project. But he is documenting black Bulloch County residents who served in World War II, not limited to fallen soldiers.

"Over a million African Americans joined the United States military at the outbreak of World War II. The majority of them went into the United States Army, and they were denied the same opportunities that their white counterparts did," Heber said. "They were usually passed over for combat roles; they were relegated to quartermaster roles and logistics and (in the Navy) cooking on ships."

But there are many famous examples of hard-won exceptions to the exclusion from combat, he noted. These included the U.S. Army Air Corps 332nd Fighter Group and 447th Bombardment Group, together known as the Tuskegee Airmen; the 92nd Infantry, known as the Buffalo Division, which participated in heavy fighting during the Allied invasion of Italy; and the Red Ball Express, which hauled supplies from Normandy through to Paris during the Allied invasion of France.

"These soldiers served the United States with distinction while also facing discrimination from within the Army," Heber said. "They couldn't use the same facilities that their white counterparts did. They were regularly attacked and harassed by their own fellow soldiers, and they were expected to fight for freedom in Europe but were denied rights back home."

This point was also driven home by another of the symposium speakers, Maxine Bryant, Ph.D., director of the Gullah-Geechee Heritage Center at Georgia Southern's Armstrong Campus in Savannah. Noting that racial violence was directed at black veterans returning home to the United States after both World Wars, she described the August 1946 lynching of honorably-discharged World War II Cpl. John Cecil Jones by a mob in Webster Parish, Louisiana, and the cover-up by officials, as well as the February 1946 beating and blinding of multiple medal-awarded veteran Isaac Woodward Jr. by police in Batesburg, South Carolina. Still in uniform, Woodward had been riding home on a Greyhound bus after being discharged at Ford Gordon near Augusta.

Both Bryant and Heber talked about this incident. It was not until 1948 that President Harry S. Truman signed Executive Order 9981 officially desegregating the military, and "it would take many years for that to fully get into effect," Heber noted. Not until 50 years after the war did a black soldier of World War II first receive the Medal of Honor, presented by President Bill Clinton, he added.

"My project is to create a physical and virtual exhibit telling the story of Bulloch County veterans from World War II. It would be hosted here at the Willow Hill Center and online through Georgia Southern," Heber said. "I intend to cover the service of Bulloch County veterans, what they did during the war, throughout their enlistment, and what they did after."

To do this, he said, he needs photos, artifacts or written accounts from or about people who served during the war. He can be reached by email at LH16980@georgiasouthern.edu.

Digitization project

Heber's current internship is one of those funded under the two-year, $92,000 grant the Institute of Museum and Library Services, a federal agency, awarded the Willow Hill Center in 2023 for work to digitize and expand its collection of printed and written programs from African American funerals dating from the 1940s forward. That collection now includes more than 20,000 funeral programs, only 6,000 of which are available online so far, said Dr. Nkenge Jackson-Flowers, Willow Hill Center board secretary and part of the family that has led in volunteer work to preserve the school site and its extant 1954 building and develop it as a museum and cultural center.

"We are evolving in terms of who we are," Jackson-Flowers said Saturday. "We are a museum, we are a cultural center, we're a historic site, but we're also an archive. And the reason these community archives are so important is that traditionally, there's a lot of history of people that made great contributions to the United States of America that have been left out of the record. There are stories that haven't been told, experiences that have not been written about, and our job here is to capture that."

Her father, Willow Hill Center board President Dr. Alvin Jackson, retraced Willow Hill's history from the founding of the original school in 1874 by formerly enslaved families for their children, through the purchase of the current school building and campus from the Bulloch County Board of Education by their descendants and other community members, and the founding of the center and its current work.

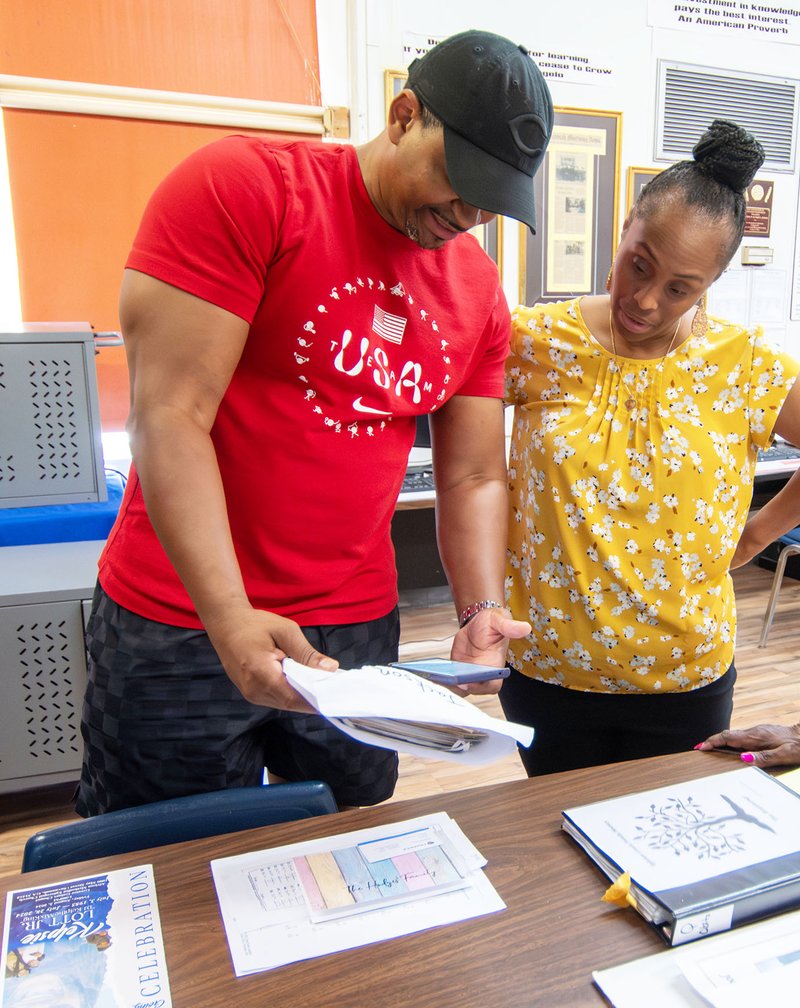

Also during the weekend, Heber and other members of the archival team scanned photographs and other materials brought in by area residents.

Video of the weekend's main events can be found on "The Willow Hill Heritage and Renaissance Center" page on Facebook.