When Dr. Alvin Jackson of the Willow Hill Heritage and Renaissance Center spoke to the Bulloch County Historical Society last month, its members and guests heard from an organization that works with the Georgia Southern Museum and the university’s History Department, as well as the Historical Society at times, to highlight and present the history of African American residents of the region.

Jackson, who was born in Portal, grew up in Bulloch County and became one of the first Black students to graduate from Statesboro High School, attended Andrews University in Michigan for his bachelor’s degree and received a scholarship that allowed him to study at the University of Keele in England and travel to over 20 countries in Europe. He then earned his M.D. from The Ohio State University and began a career as a family practice physician, also serving several years as director of the Ohio Department of Health.

But he maintained ties to Bulloch County and family and friends here. He credits a project one of his daughters, now Dr. Nkenge Jackson-Flowers, completed 37 years ago with launching much of the Willow Hill project that has involved several family members for decades. Then a young teenager attending school in Ohio, her project on the historic Willow Hill School in Bulloch County, Georgia, won a 1988 National History Day prize, awarded in Washington, D.C., with research on the history of the school. Her father had suggested the topic. They both also contributed to Dr. F. Erik Brooks' book, "Defining their Destiny: The Story of the Willow Hill School."

Speaking to the Historical Society, Jackson dedicated his presentation, “Celebrating 150 Years of History … the Story of the Willow Hill School and Community,” to his wife, Gayle Jackson, who served as the Willow Hill Center’s development director until her death in August 2023.

150 years of history

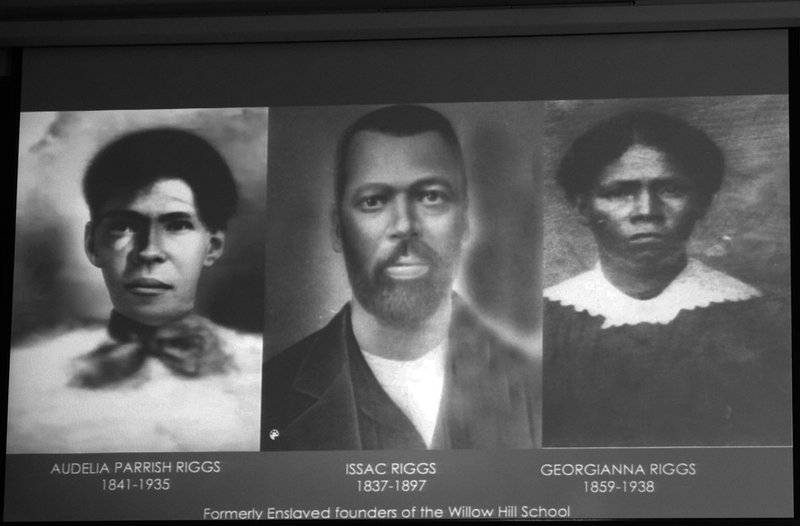

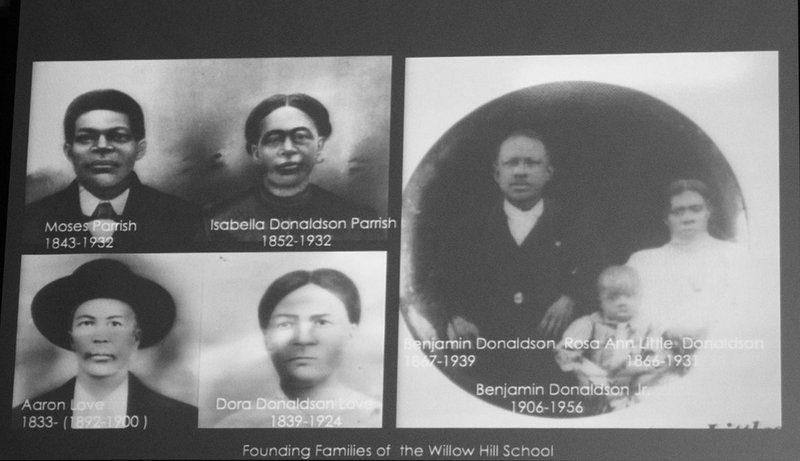

Roughly a decade after the abolition of slavery, formerly enslaved residents of the Willow Hill area near Portal established the school for their children. The core families included the Donaldsons, the Riggs, the Halls and the Parishes.

These “families, post-slavery, they became landowners and owned up to six thousand acres of land in the Willow Hill community,” Jackson said. “They founded the Willow Hill school in 1874 as one of the first schools in Bulloch County for African Americans, just a few years after the Civil War.”

The original building was a wooden turpentine shanty, “with one door, one window,” on land owned by Dan Riggs, one of the founders. Georgianna Riggs was just 15 years old when she became the first teacher at the school.

One of the later facilities was a “Rosenwald school” built as were many African American community schools in the South in the early 20th century with help from the Rosenwald Fund, but Jackson said community residents did most of the fundraising. The existing building is the state-funded one built as an “equalization school” following the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education. Although the court had thrown out the old “separate but equal” doctrine, Georgia and other states made a belated attempt to improve school facilities for African Americans.

Willow Hill continued in operation as a public elementary school, racially integrated from 1971, until 1999.

The renaissance

“In 2005, the direct descendants of the school’s founders, 12 of us, organized ourselves and bought the school from the Bulloch County Board of Education when they put it on the auction block, to start a Willow Hill Heritage & Renaissance Center,” Jackson said. “‘Heritage’ is about paying honor to our ancestors and what they did. Many of them couldn’t read and write, but they knew the value of an education and they started that, and ‘Renaissance’ is about new opportunities, doing the Techie Camp and other kinds of things we do at the center.”

With a slideshow, he shared images of the school, the oldest known photo of which is from 1905, and its people, and also told stories of its core families, including his own ancestors. Over the years, Jackson and volunteers have recorded oral histories from descendants of the Willow Hill families, including some local individuals and many now resident in other parts of the United States. This vast archive now includes more than 500 recordings, he reports.

To the left in one historic photo was a man named Jonas Lee.

“That’s my great-grandfather,” Jackson said. “His father was a Black cowboy. Before they had fences here in Bulloch County and the cows roamed, they used to herd them to Savannah, Georgia, across the Ogeechee River, and my great-grandfather, his father known as Cow Jack Lee, they used to work together. According to the oral recordings I have, my great-grandfather rode a mule and his dad, Cow Jack, rode a horse.”

Some sadder but significant events from the history of the Willow Hill School and its community made the newspapers over the decades. One of the school’s formerly enslaved founders, Isaac Riggs, was beaten at his home by six white men on May 13, 1876, for his role in teaching black children, the Colored Tribune in Savannah reported that June 3. One of the best-known historic images from Jackson’s slide show is of a cross burned by the Ku Klux Klan outside the school in March 1946 when Black people from Bulloch County met there to plan to vote in significant numbers for the first time since the 1890s.

“Nevertheless, they did,” he said.

Ongoing programs

Now the Willow Hill Center has ongoing programs and projects for both its “heritage” and “renaissance” aspects.

“We’re a museum, a historical site, we have on our campus the Bennett Grove School, which is the last one-room African American school in Bulloch County,” Jackson noted. “We are a cultural center. We offer tours.”

The center’s next annual event will be “A Taste of Struggle,” the last Saturday in April. This features cooking in a pit outside “as they did during days of slavery,” he said. Meals are offered for a donation and other information of “life as it used to be,” is shared by presenters.

Look for further information on a Juneteenth celebration. Last year the Bulloch County NAACP hosted one on the center’s campus.

Techie Camp, for which Jackson noted his late wife obtained a grant, is a summer day camp for elementary and middle school students held at the center, using its WiFi-equipped outdoor pavilion, that includes instruction in computer coding and other technology-based projects.

He is continuing ‘If These Cemeteries Could Talk,” a sometimes monthly series of tours of predominantly African American cemeteries in Bulloch County.

The Willow Hill Heritage & Renaissance Center also continues to add to its collection of printed – and sometimes in the case of older ones, handwritten – programs from African American funerals.

“We are one of about … six sites in the whole state of Georgia, and we at Willow Hill have the largest collection of all,” he said, “and these are really important for genealogical and sociological reasons. Now, with African Americans, for most folk, if you are not very famous, the place where your history is written down is in your obituary.”

Georgia Southern public history graduate student Lawrence Heber, who has been interning with the Willow Hill Center for three years, also attended the luncheon meeting where Jackson spoke. He has been helping to digitize funeral programs under the center’s grant-funded digitization project. Huber’s project toward his master’s degree focuses on the experiences of African American service members from Bulloch County during World War II.

Dr. Brent Tharp, director of the Georgia Southern Museum and vice president of the Bulloch County Historical Society, led the Feb. 24 meeting and introduced Jackson as “our friend and colleague.”