Fully 50% of the Bulloch County residents who died in military service during World War I – 13 of the 26 local men – were African American. But only two of the black soldiers from Bulloch County who lost their lives during the war, namely Willie Brannen and Clarence Lyons, were killed in combat. The others died of disease, in most cases influenza, while in service.

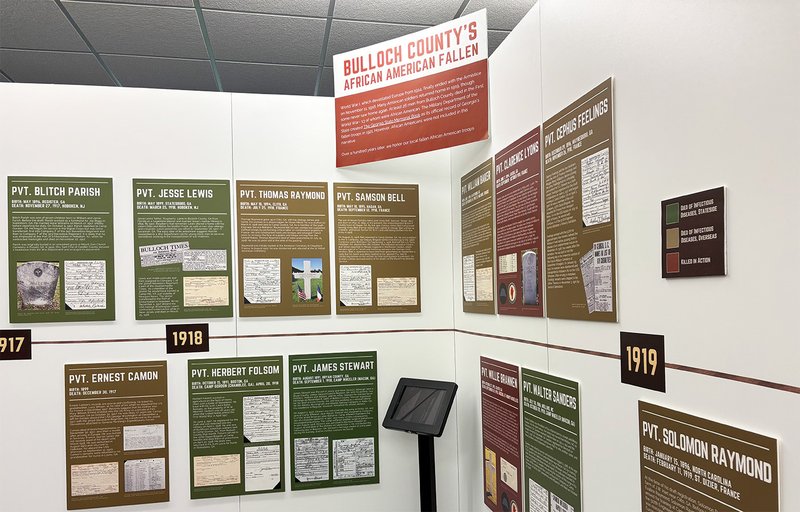

Those were among the heroic and tragic facts that Georgia Southern University history professor Brian K. Feltman, Ph.D., included in his recap of “More Than a Name: The Experiences of Bulloch County’s African American Soldiers of the First World War,” Monday for the Bulloch County Historical Society. The similarly named exhibit assembled by Feltman’s students with support from the Special Collections unit of the GS University Libraries is now in its final week, having been up on the second floor of the Zack Henderson Library on the Statesboro campus since April 1 and promised to remain there until Aug. 1.

That exhibit and the students’ research actually grew out of an earlier project, roughly two years ago, in which Feltman worked with a different group of students who collected information on Bulloch County’s involvement in World War I, including identifying all of the fallen soldiers regardless of race. That became the “Bulloch County World War I Memorial Project: A Digital Exhibition and Resource Guide.”

With about 29 students in his History of World War I class at that time, he assigned 26 students each one of the Bulloch County fallen soldiers to research, while the other few students researched topics about life in Bulloch County during the war, which began in July 1914, with the U.S. directly involved from April 1917 until the concluding armistice in November 1918.

“Now, what we found when … we were trying to build biographies of these men is that it was very easy to come up with very detailed biographies for white soldiers,” Feltman said. “You had in many cases letters, photographs, newspaper articles, and we got a lot more information from the Dexter Allen Auxiliary Collection over in special collections. So we had an immense amount of information for most of the white soldiers.”

Dexter Allen, a young white man, was the first soldier from Bulloch County to die on the battlefield in World War I. So the local American Legion post, Dexter Allen Post 90, was and remains named for him.

“But what most people don’t know is that months before Dexter Allen ever fell on the battlefield in France, two young African American men from Bulloch County had already died in service to their country,” Feltman said.

However, as he noted, those two young men, Ernest Camon and Blitch Parrish, died of other causes, not in combat, as was the case with the large majority of the black soldiers who died and many of the white soldiers as well.

“I’m willing to bet that … most of you have never heard of these two men, and that was something that really concerned us. When we were going through and putting these biographies together, we realized that most of the African American fallen from the First World War, here in Bulloch County, had essentially been forgotten,” Feltman said. “They were not part of the historical record, and so we set out to remedy that situation.”

He and the other researchers applied for and were awarded a grant from the Georgia Humanities Council, and also received some additional funding from the GS Department of History, the University Libraries and the GS College of Arts and Humanities for the project focusing on Bulloch’s fallen black soldiers of World War I.

Numbers in perspective

Approximately 380,000 African Americans served during World War I. About 34,000 were from Georgia, of whom approximately 1,100 “would see actual combat,” according to Feltman.

“Here in Bulloch County, there were 240 African American veterans,” he said.

The service of black soldiers was a very contentious issue at the time, with Jim Crow racial segregation the law throughout the South and in many ways national policy. But by 1916, the government had realized that a draft would be needed to build up the Army for the likelihood of the United States being drafted into the war. After the declaration of war in April 1917, all men of military age were required to register for selective service. The date they had to report to a local administrative office was June 7, 1917.

On that day in Bulloch County, 1,310 white men and 932 black men registered, for a total of 2,242 men ready for the draft.

With so many African American men showing up to register, a Statesboro newspaper of 1917 published a brief report both reflecting the racism of the time and providing a countercurrent to it, as Feltman displayed on a slide. Under the subhead, “Negroes are loyal,” the story segment began: “The spirit which Bulloch County’s colored population showed on registration day should be set down in red letters for the country and for themselves as a race. There was not only no disloyalty, but no apathy or indifference suggested in their record for the day. They were ready and eager to do their part and those who are called will not be found wanting.”

Only 10% allowed to fight

Still, “because of that fear of giving an African American man a weapon and teaching him how to use it,” 90% of all black U.S. troops who served were deployed in non-combat roles. Most were placed in “labor battalions” for tasks such as building roads and loading and unloading supplies from cargo ships. Later, a number of these troops were ordered to the grim task of disinterring the bodies of fellow Americans who were buried in temporary graves on battlefields for reburial in American cemeteries in Europe or for return to the United States.

African American soldiers were mostly assigned to two large, segregated units, the 92nd Infantry Division, nicknamed “Buffalo Soldiers” after the 19th century African American cavalry units, and the 93rd Infantry Division.

The Bloody Red Hand

The first African American soldiers of World War I allowed to serve in combat actually served under French command. These soldiers from the 93rd Division were nicknamed "Blue Helmets" because of the French helmets they received. Some served with the French 157th Division, the “Bloody Red Hand,” whose division flag included a red hand in the middle and a small U.S. flag in the top hoist corner, and whose black American troops were awarded the Croix de Geurre, a medal for valor in combat, by France.

“When it comes to Bulloch County, two men from our county lost their lives while serving with the Bloody Red Hand,” said Feltman. “Those men were Private Clarence Lyons and Private Willie Brannen.”

Lyons, born June 7, 1894, in Avera, Georgia, but later a Bulloch resident, was killed in action in France in September or October 1918. His family later had his remains returned to the United States, and he is buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Brannen, born Oct. 27, 1895, at Oliver in Screven County but who as a young adult resided on Elm Street in Statesboro, died in combat Sept. 30, 1918, at Ardeuil-et-Montfauxelles. His grave is in the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery in France. Their two names are marked in red among the 13 names on the panel of Bulloch County’s black soldiers who died in the war.

The Spanish flu

“Everyone else on this list died of disease, and when you’re looking at the records, usually they would write, ‘pneumonia,’ and we now known that it was very likely the Spanish flu that was sweeping across Europe, sweeping here into the United States,” Feltman explained. “And so, pneumonia was kind of a catch-all phrase at that time, meaning, ‘There’s something wrong with their lungs and they’re dying; we don’t really understand what’s going on.’”

Those other 11 were William Baker, Samson “Simon” Bell, Ernst Camon, Cephas Feelings, Herbert Folsom, Jesse Lewis, Blitch Parrish, Solomon Raymond, Thomas Raymond, Walter Sanders and James Stewart.

Building the biographies, the student and faculty researchers found much of their information by searching for the men’s service records and burial and disinterment records in the National Archives.

After it is taken down at the Henderson Library, the exhibition is expected to travel to the Willow Hill Heritage & Renaissance Center near Portal for future display.

Online versions of the “Bulloch County World War I Memorial Project” and “More than a Name” can be found by a search for either of those titles at https://georgiasouthern.libguides.com.