The Bulloch County Historical Society during its 49th annual meeting, June 26, heard a professional historian’s report on how Georgia’s white-tailed deer population had nearly vanished a century ago, was re-established through human intervention and rebounded to record, and problematic, numbers.

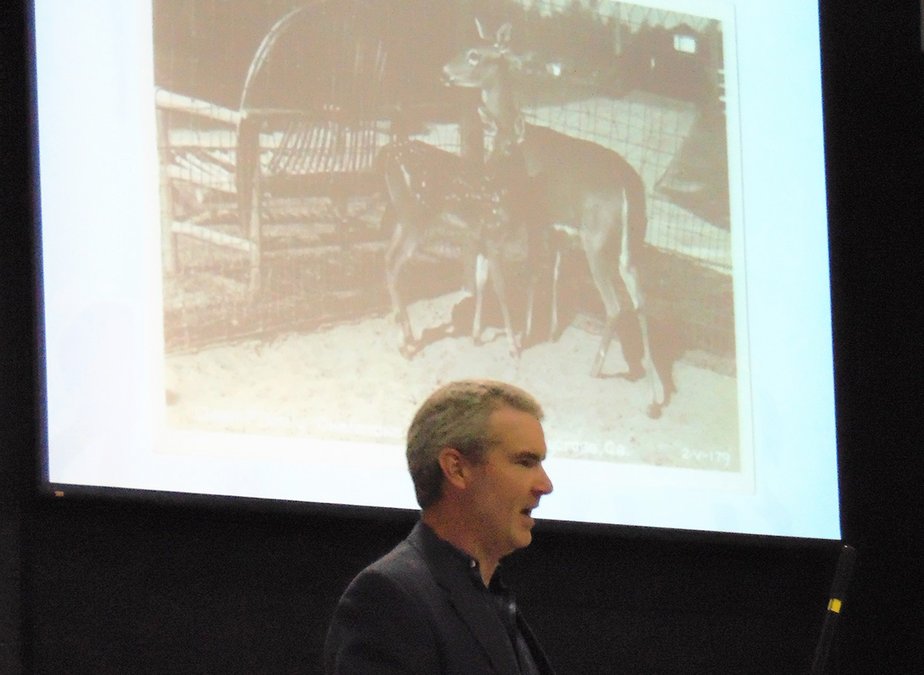

Drew Swanson, Ph.D., the Jack N. and Addie D. Averitt Distinguished Professor of Southern History at Georgia Southern University, entitled his presentation, “Deer at Any Price: The Recovery of Georgia’s White-Tailed Deer.”

Born in rural Virginia, Swanson had worked as a farmer, zookeeper and natural resource manager “before turning to academia,” Historical Society Vice President Brent Tharp, Ph.D., noted in his introduction. With three published books to his credit, Swanson is now working on two more, one of which will be about white-tailed deer.

“I’ve spoken to audiences in places like Greece and Norway and Finland about deer, but it’s a real pleasure to be back in their native range to speak to people who know deer a little more intimately, who’ve spent maybe time in the woods with whitetails or chased them out of your garden, or God forbid, may have hit them with your cars at some point in your life,” Swanson said.

Noting that deer have become so common in Georgia that they can be “somewhat easy to take for granted” or even “something of an annoyance,” he began with “a simple but pretty dramatic set of statistics” to show what makes them historically interesting.

When Christopher Columbus landed at Hispaniola in 1492, there were, by modern estimates, 30 million or so white-tailed deer scattered across North America, from Panama into Canada. But by shortly after 1900, “sort the low point of a long decline in those numbers,” Swanson said, there were only around 300,000 whitetails, about 1% of the original population.

Only about 3,000 of those were in Georgia, according to Swanson.

“Fast forward to today and there are an estimated 30 to 35 million whitetails in the continental United States alone,” he said. “So to put it another way, there are more deer today than there have been at any point in human history.”

The long decline

The decline of the deer population began with the colonial trade in deer hides. By the early 1700s, deer of European species were virtually gone from England, the few remaining animals being restricted to deer parks where they were officially owned by the king, Swanson noted. So this contributed to the demand for deerskin – “the premier leather of its day” – from America for things such as book covers, gloves, saddles and shot pouches.

“By the 1770s, about 700,000 pounds of dressed deerskins were being exported from Southern ports, including Savannah, each year, and the export trade consumed an estimated six to 10 million deer between 1700 and 1775,” Swanson said. “And keep in mind, that’s just the deer heading off to Europe through the ports and being counted, and not deer being killed for internal purposes, which was certainly a larger number.”

Then in the 1800s, a domestic “market hunting trade” developed, supplying venison for consumption in cities. Georgia’s first law on market hunting, requiring the hunters to buy a license for $25, was enacted in 1899, with many loopholes rendering it completely ineffective, he said.

In 1910, more than two-thirds of Georgia counties reported there were no deer left within their boundaries, Swanson said. Pockets of deer populations remained along the Ogeechee and Altamaha River basins, but the largest remaining concentrations were on the Sea Islands.

Restoration efforts

Nationally, the first big effort at deer restoration began in Vermont in the 1870s, followed a few years later in states like New York and Pennsylvania, with the South following suit about 20 years behind the Northeastern states, he said.

Arthur Woody, a U.S. Forest Service ranger in the Chattahoochee National Forest in northernmost Georgia, is credited as the “founding father” or whitetail restoration in Georgia. In 1928, he purchased six or eight deer, some of them from the Pisgah National Forest in North Carolina and some from a roadside carnival, and released them in the Chattahoochee region.

But Swanson observed that federally funded New Deal programs during the Great Depression were the real drivers of restoration, and regular deer releases in the Chattahoochee National Forest began in 1933.

Then the Pittman-Robertson Act, a federal law passed in 1937 and still in effect, placed an 11% tax on firearms and ammunition and dedicated the money to wildlife conservation and restoration programs.

“Georgia qualified for Pittman-Robertson money in 1943 and then began to spend a lot of that money on its deer program,” he said.

The state purchased roughly 450 deer in the first five years of the program, and a tranquilizer gun used in deer relocation was developed in Georgia. By the 1950s, Georgia’s deer population had increased tenfold, to about 30,000, and restoration efforts continued into the 1970s, with the population then growing steadily.

Pittman-Robertson money also went to purchase land for wildlife, establishing game refuges that became the Wildlife Management Areas. Over the years, the revenue allowed the state to hire wildlife biologists and fund studies into deer reproduction, nutrition and health.

“We know that these programs were extraordinarily successful, at least in terms of bringing deer back – maybe too successful, depending on who you ask,” said Swanson. “Georgia’s current deer population is approximately 1.3 million animals.”

It may have peaked in the early 1990s, possibly as high as 1.9 million, he added.

Swanson talked about the economic importance of deer, literally the target of a multi-billion-dollar hunting industry.

Then he noted that deer’s grazing habits make them an annoyance to farmers and homeowners and that deer carry ticks, which vector certain illnesses.

He also presented an insurance company map that shows Georgia as a “high risk” state for deer-vehicle collisions. But nearly half of the United States is in that category, he noted, not all from whitetails but from various deer species in different regions of the country.

Finally, he remarked that history suggests the deer population could be fragile, since restocking efforts were still underway just 50 years ago, and the “large, dense herds of recent years contain the prospect” of an epidemic “that could lower their numbers as quickly as they increased.”

Scholarship winners

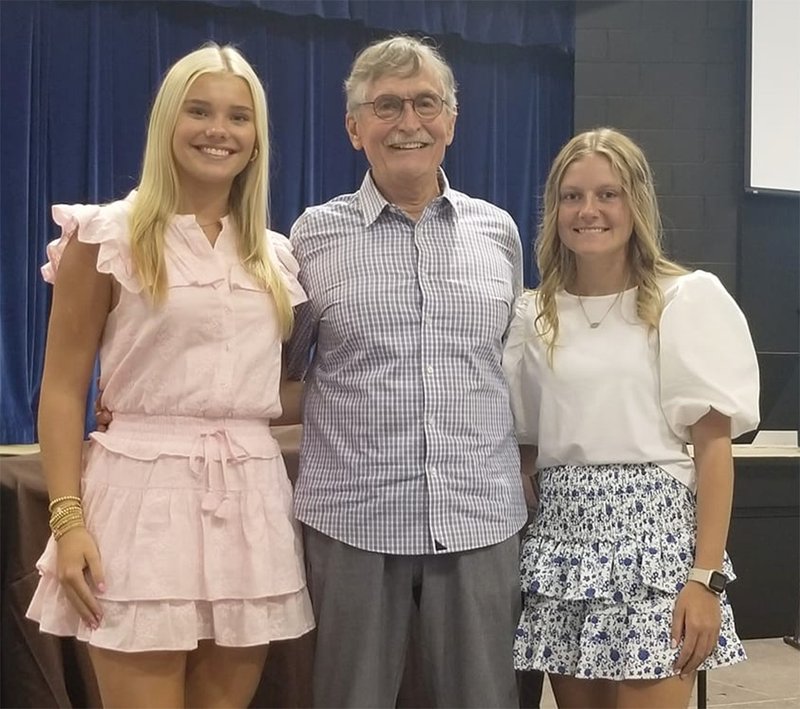

Also during its annual meeting, the Bulloch County Historical Society awarded its first scholarships in a new essay-based program for graduating seniors from local high schools. Scholarship committee chairman Fred Richter, Ph.D., presented the first-place, $2,000, check to Avery White, a 2023 graduate of Statesboro High School, and the second-place, $1,500, check to Marlie Motes, a 2023 graduate of Portal High School.

“We wanted to encourage interest in history, so we sought out high school seniors who were particularly interested in history and we offered them several choices of topic,” Richter said.

White chose the question, “Where in history would you like to visit?” and chose to visit the Wright brothers at the time of their first flight. Daughter of Johnny and Melanie White, she plans to attend the University of Georgia to study criminal justice on the pre-law pathway.

Motes, a softball player and baseball fan, chose the question, “With what historical figure would you like to have a conversation?” and wrote about Jackie Robinson. Daughter of Travis and Mandy Motes, she is enrolled at East Georgia State College-Statesboro with hopes of going into the dental program at Augusta University.