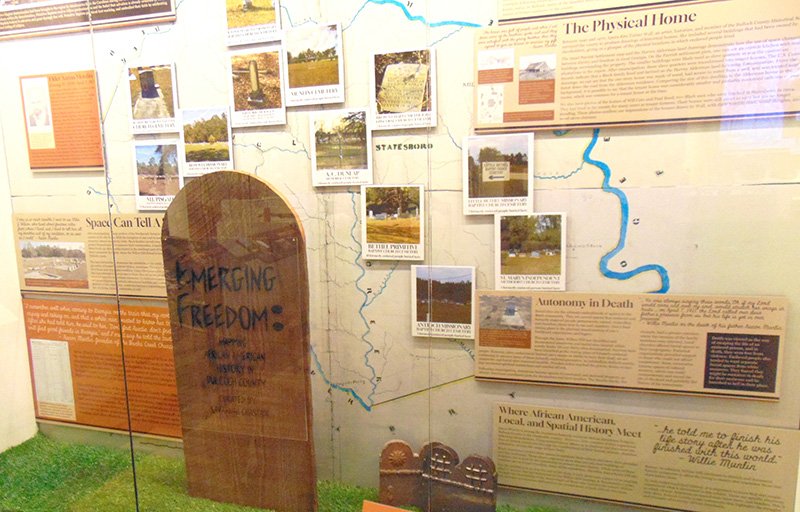

With her research project, “Emerging Freedom: Mapping African American History in Bulloch County,” Savannah Chastain has created a museum exhibit and story map offering glimpses into various aspects of the lives of residents of the area emerging from slavery in the 19th century and into 20th.

Chastain, who attained a Bachelor of Arts in history at the University of North Georgia in 2021, came to Georgia Southern University for her Master of Arts in history with a concentration in public history. She had graduated with that degree so recently that she had yet to receive the actual diploma when she spoke to the Bulloch County Historical Society on May 20. While studying for her MA, Chastain worked as the education graduate assistant and social media coordinator for the Georgia Southern Museum, as its director, Brent Tharp, Ph.D., noted in introducing her to the Historical Society.

Furthermore, Chastain’s project of research, mapping and public education began in cooperation with the Willow Hill Heritage and Renaissance Center. This is the museum and community center near Portal at the historic Willow Hill School, whose original incarnation was founded by formerly enslaved families for their children in 1874.

The Willow Hill Center’s board president, Dr. Alvin Jackson, has led in identifying African American cemeteries in Bulloch County, now upwards of 35 of them. He has also conducted a series of tours called “If These Cemeteries Could Talk” to speak the names of formerly enslaved people and their descendants and tell their stories at their gravesites.

Chastain’s project grew from the idea of mapping the locations of the cemeteries, 14 of which are known to include the graves of people who were enslaved for at least part of their lives.

“While doing this, though, I started seeing patterns and wanted to broaden the scope by not just looking at cemeteries but also looking at how other important spaces in African American history are showcased in Bulloch County,” she said.

A real showcase

Now, her compact exhibit is displayed in a literal glass-front showcase just inside the entrance to the continuing “Charted Worlds: The Cultural History of Georgia’s Coastal Plain” exhibition gallery at the Georgia Southern Museum. The “Emerging Freedom: Mapping African American History” exhibit is scheduled to remain there for one year and then be transferred to the Willow Hill Center for permanent display.

The broadening of Chastain’s “spatial history” research beyond cemeteries led to “a wealth of topics: education, church, labor history, family and housing history and, obviously, Bulloch County history,” she said. It also led to a recognition of certain pivotal personalities and historical sources.

Elder Aaron Munlin

One standout figure in her findings is Elder Aaron Munlin, 1848-1911, who was born in slavery and later became a Primitive Baptist minister and founder of Banks Creek Primitive Baptist Church, said to be the first Black-led Primitive Baptist church in the area.

“Elder Aaron Munlin’s is the only slave narrative that comes out of Bulloch County, at least that I’ve been able to find,” said Chastain. “Munlin’s son published it in 1912, right after Munlin’s death, and the Bulloch County Historical Society republished it in 1973.”

In it, Munlin “basically talks about the people that enslaved him, listing their names in about a paragraph, and then goes on to actually talk about his religious journey,” she said

As Chastain notes, Munlin also made observations relevant to the other topics she explored, such as education and the working lives of African Americans in the area. So she included a quote from his papers in each panel of her exhibit “because I wanted to make sure that that story was being told not just from my perspective but from someone else’s, who was actually living it,” Chastain said.

Churches with schools

She found that African American churches often served as their communities’ first school buildings, so at church locations such as Johnson’s Grove and St. Mary’s in northern Bulloch County and Little Bethel towards the south, she was able to map both church and school sites.

Chastain also observed that Bulloch’s earliest African American churches and schools were found mainly in the northern part of the county and later-established ones to the south, but she did not do research to determine if this was the result of any kind of migration. A 1915 educational survey of Bulloch County identified schools existing at that time.

Many formerly enslaved people worked as tenant farmers, so their homes were usually simple ones referred to as tenant houses. She discovered references to an earlier local researcher, Rita Turner Wall, while looking into family histories at the Statesboro-Bulloch County library, and found Wall’s drawings of tenant houses useful in knowing what these looked like.

Actual artifacts from formerly enslaved individuals are scarce, she noted. Ceramic garden tiles included in the exhibit are actually from Fort Stewart but are like those used for grave decorations in Bulloch County and elsewhere, she said.

Her exhibit includes lists of the names of formerly enslaved persons known to be buried in the cemeteries, and additional information from her research can be accessed by scanning a QR code on one end of the showcase. The Georgia Southern Museum is open 9 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesday-Friday and 2-5 p.m. Sunday, including most of the summer.