CHICAGO — Every child should be tested for high cholesterol between ages 9 and 11 so steps can be taken to prevent heart disease later on, a panel of doctors urged Friday in new advice that is sure to be controversial.

Until now, major medical groups have suggested cholesterol tests only for children with a family history of early heart disease or high cholesterol and those who are obese or have diabetes or high blood pressure. But studies show that is missing many children with high cholesterol, and the number of them at risk is growing because of the obesity epidemic.

The recommendation is in new guidelines from an expert panel appointed by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute and endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

They also advise diabetes screening every two years starting as early as 9 for children who are overweight and have other risks for Type 2 diabetes, including family history. One third of U.S. children and teens are obese or overweight, fueling a boom in diabetes.

Autopsy studies show that some children already have signs of heart disease even before they have symptoms. By the fourth grade, 10 percent to 13 percent of U.S. children have high cholesterol, defined as a score of 200 or more.

Fats build up in the heart arteries in the first and second decade of life but usually don't start hardening the arteries until people are in their 20s and 30s, said one of the guideline panel members, Dr. Elaine Urbina, director of preventive cardiology at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center.

"If we screen at age 20, it may be already too late," she said. "To me it's not controversial at all. We should have been doing this for years."

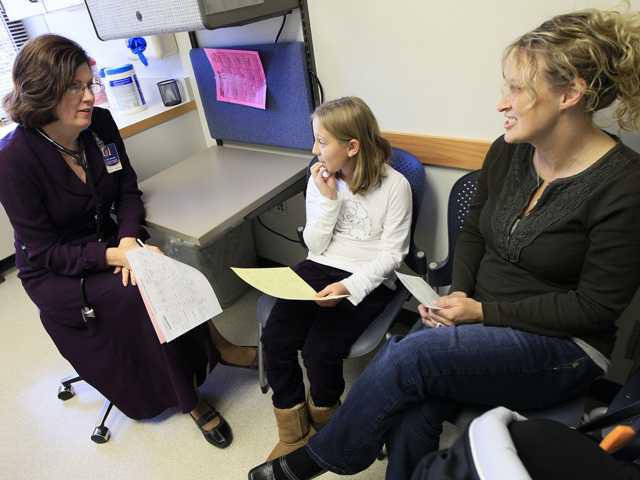

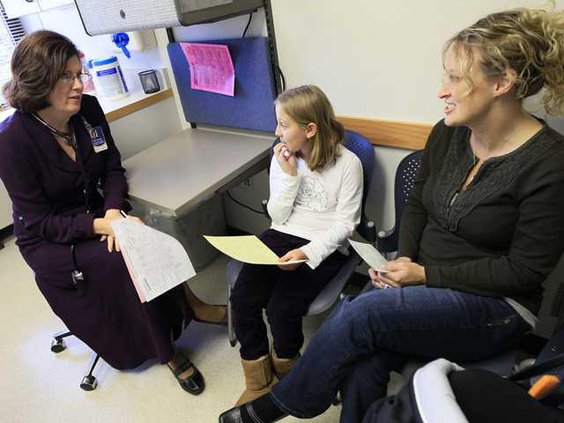

Elizabeth Duruz didn't want to take that chance. Her 10-year-old daughter, Joscelyn Benninghoff, has been on cholesterol-lowering medicines since she was 5 because high cholesterol runs in her family. They live in Cincinnati.

"We decided when she was 5 that we would get her screened early on. She tested really high" despite being active and not overweight, Duruz said. "We're doing what we need to do for her now and that gives me hope that she'll be healthy."

Doctors recommend screening between ages 9 and 11 because cholesterol dips during puberty and rises later. They also advise testing again later, between ages 17 and 21.

The guidelines say that cholesterol drugs likely would be recommended for less than 1 percent of kids tested. Most children found to have high cholesterol would be advised to control it with diet and physical activity.

And children younger than 10 should not be treated with cholesterol drugs unless they have severe cholesterol problems, the guidelines say.

"We'll also continue to encourage parents and children to make positive lifestyle choices to prevent risk factors from occurring," said Dr. Gordan Tomaselli, president of the American Heart Association, which praised the guidelines and will host a presentation on them Sunday at its annual conference in Florida.

Cholesterol tests cost around $80 and usually are covered by health insurance.

Several doctors on the guidelines panel have received consulting fees or have had other financial ties to makers of cholesterol medicines, and the new advice raises concerns about overtreating children with powerful drugs without long-term evidence about potential effects from decades of use.

Typically, cholesterol drugs are used indefinitely but they are generally safe, said Dr. Sarah Blumenschein, director of preventive cardiology at Children's Medical Center in Dallas.

"You have to start early. It's much easier to change children's behavior when they're 5, or 10, or 12" than when they're older, said Blumenschein, who treats many children with high cholesterol and supports the screening advice.

A different group of government advisers, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, concluded in 2007 that there's not enough known about the possible benefits and harms to recommend for or against cholesterol screening for children and teens.

One of its leaders, Dr. Michael LeFevre, a family medicine specialist at the University of Missouri, said that for the task force to declare screening beneficial there must be evidence that treatment improves health, such as preventing heart attacks, rather than just nudges down a number — the cholesterol score.

"Some of the argument is that we need to treat children when they're 14 or 15 to keep them from having a heart attack when they're 50, and that's a pretty long lag time," he said.

The guidelines also say doctors should:

—Take yearly blood pressure measurements for children starting at age 3.

—Start routine anti-smoking advice when kids are ages 5 to 9, and counsel parents of infants not to smoke in the home.

—Review infants' family history of obesity and start tracking body mass index, or BMI, a measure of obesity, at age 2.

The panel also suggests using more frank terms for kids who are overweight and obese than some government agencies have used in the past. Children whose BMI is in the 85th to 95th percentile should be called overweight, not "at risk for overweight," and kids whose BMI is in the 95th percentile or higher should be called obese, not "overweight — even kids as young as age 2, the panel said.

"Some might feel that 'obese' is an unacceptable term for children and parents," so doctors should "use descriptive terminology that is appropriate for each child and family," the guidelines recommend.

They were released online Friday by the journal Pediatrics.