SEATTLE — Supporters have offered $1 million for her release. Annual demonstrations have demanded her return to the Northwest. Over the years, celebrities, schoolchildren and even a Washington state governor have campaigned to free Lolita, a killer whale captured from Puget Sound waters in 1970 and who has been performing at Miami Seaquarium for the past four decades.

Activists are now suing the federal government in federal court in Seattle, saying it should have protected Lolita when it listed other Southern Resident orcas as an endangered species in 2005.

"The fact that the federal government has declared these pods to be endangered is a good thing, but they neglected to include these captives," said Karen Munro, a plaintiff in the lawsuit who lives in Olympia, Wash. Plaintiffs include two other individuals, the Animal Legal Defense Fund and People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals

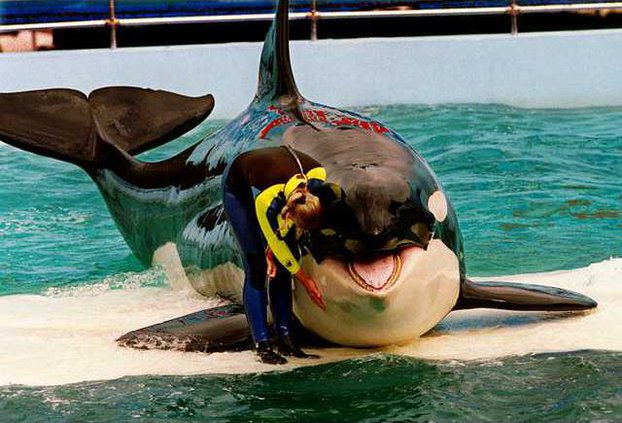

The lawsuit filed in November alleges that the fisheries service allows the Miami Seaquarium to keep Lolita in conditions that harm and harass her and otherwise wouldn't be allowed under the Endangered Species Act. The lawsuit alleges Lolita is confined in an inadequate tank without sufficient space and without companions of her own species.

The agency is still reviewing the lawsuit, said Monica Allen, a spokeswoman with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, whose fisheries service oversees marine mammals.

Lolita, who is estimated to be about 44 or 45, is the last surviving orca captured from the Southern Resident orca population during the 1970s. She is a member of the L pod, or family. Female orcas generally live into their 50s though they can live decades longer.

The J, K, and L pods frequent Western Washington's inland marine waters and are genetically and behaviorally distinct from other killer whales. They eat salmon rather than marine mammals, show an attachment to the region, and make sounds that are considered a unique dialect. The whales, with striking black coloring and white bellies, spend time in tight, social groups and ply the waters of Puget Sound and British Columbia.

When the National Marine Fisheries Service listed the Southern Resident orcas as endangered — in decline because of lack of prey, pollution and contaminants, and effects from vessels and other factors — it didn't include whales placed in captivity prior to the listing or their captive born offspring.

They're "not maximizing opportunity to protect the species if you exclude captive members," said Craig Dillard, litigation director for the Animal Legal Defense. Lolita should have the same protections as other wild orcas, he added.

He noted that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is currently considering whether to give all captive chimpanzees the same protection as wild chimpanzees.

The Miami Seaquarium declined to comment on the lawsuit. It issued a statement saying Lolita is active, healthy, well-cared for and plays an important role in educating the public about the need to conserve the species. Lolita has learned to trust humans completely, the statement says, and "this longstanding behavioral trust would be dangerous for her if she were returned to Puget Sound, where commercial boat traffic and human activity are heavy, pollution is a serious issue and the killer whale population has been listed as an endangered species."

Howard Garrett, co-founder of the nonprofit Orca Network based on Whidbey Island, Wash., said returning her to Northwest waters is the right thing to do. It would be healthier for her, and allow her to rebuild family bonds with the L pod.

"She remembers where she came from. I think she will remember her water and her family," said Garrett, who has spent years advocating for her release and whose group plans to help Lolita transition back to Northwest waters.

Munro joined the lawsuit because she believes Lolita deserves to retire and return to the Puget Sound, where she can swim naturally and attempt to reunite with her family.

She became an advocate for the majestic creatures, after witnessing a "very violent, distressing scene" of orcas being torn from their pods while out sailing in 1976. The captors used explosives, boats and seaplanes to chase the animals into shallower waters and netted them, she said.

"They were taking these orcas away purely for money and profit, because they make huge amounts of money from whale shows. They (orcas) don't belong in these aquariums," she said, adding "Lolita deserves to come back."

Whale activists file suit to free Lolita

Sign up for the Herald's free e-newsletter