BAGHDAD — The mission was to get Simba al-Tikriti out of Iraq and to a new life in Britain.

First, a roadside bomb nearly wiped out the taxi heading to the border with Kuwait. The next step was to hide under tarps in the back of a truck. More hardship awaited: six months caged by authorities in England.

But freedom eventually came for Simba, who walked away from captivity with tail held high.

So began the improbable work of the self-proclaimed Cat Lady of Baghdad.

‘‘Some people buy flash cars, others flash clothes. But it’s my animals that float my boat,’’ said Louise, a security consultant in Baghdad who moonlights as a one-woman animal rescue unit that may be the only such organized effort under way in Iraq.

Since Simba’s journey three years ago, she has managed to send four more cats and two dogs back to her native England. The costs — which can run up to $3,500 per animal — are covered by donations and her ‘‘old stuff’’ sold on eBay.

‘‘Collectibles, Cabbage Patch Kids, toys, the lot,’’ said Louise, who asked that only her first name be published because of security worries.

Louise — a tall, blond and blunt-speaking former soldier with an accent as thick as Yorkshire pudding — also has private battles to wage with Iraqi bureaucracy. Completing mountains of paperwork, calls to countless officials and, on one occasion, bursting into tears at the airport have all been required to get animals out of the war zone.

By law, any animal imported to Britain must go through a six-month quarantine. There are also required vaccinations.

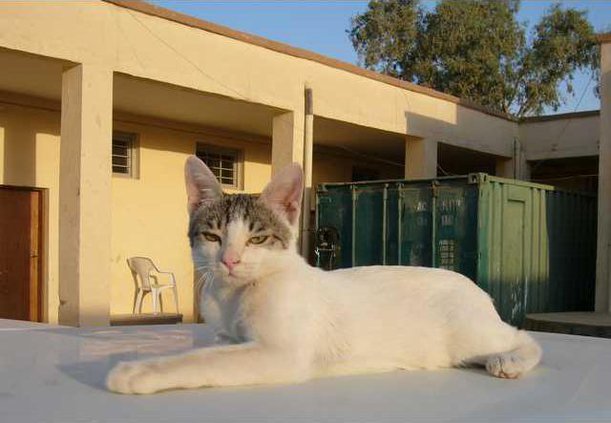

It all started when Simba, a white cat with ‘‘tabby bits,’’ strolled onto a U.S. military base. Soon came the planning for Operation Puss ’n’ Boots — as the Simba journey was dubbed by Louise’s colleagues when she worked at the Army outpost near Tikrit, about 80 miles north of Baghdad.

An Iraqi working with Louise was heading to Basra in southern Iraq. She asked if he could take Simba to the border with Kuwait, where an English friend would be waiting.

Just south of Baghdad, a car bomb exploded a few yards from the cab, but no one was hurt. At the border, Simba crossed into Kuwait with the cat hidden.

There may even be a bit of aristocracy among the felines she has rescued.

A popular urban myth in the Green Zone is that the area is overrun with cats because Saddam Hussein kept hundreds in and around his former presidential palace, which now houses the U.S. Embassy.

‘‘Two of my cats — Googles and George — have Ocicat markings,’’ Louise said, referring to a highly prized spotted breed that originated by interbreeding Abyssinian, Siamese and American Shorthair cats. The theory goes that few in Iraq, other than Saddam, would have had such a cat.

It is impossible to gauge how many dogs, cats and other animals have been rescued in Iraq in the past five years by soldiers and foreigners.

In March, Marine Maj. Brian Dennis, was reunited with Nubs after his family and friends raised the costs to fly the 2-year-old mutt from Iraq to San Diego. Dennis found the hound stabbed with a screwdriver in Iraq’s Anbar province and nursed him back to health. He named him Nubs after learning someone cut the ears off believing it would make the dog more aggressive and alert.

Many Western companies also have one or more pets living in their compounds, and cats and dogs are often seen on military bases.

It can be a strong dose of culture shock for many Iraqis who are unaccustomed to having pets and who especially — following widely held Muslim tradition — eschew dogs as unclean.

In January, Iraqi security guards and maintenance workers watched with bemusement as Zeus — one of the dogs Louise rescued — was lavished with belly scratches and other doggy treats by Westerners before it was flown to England.

But when Iraqi workers came near, Zeus would bark savagely and nip at their heels. Louise denied that the pooch had something against Iraqis.

‘‘He just senses their fear, that’s all,’’ she said.

According to an official with the Jordan office of the London-based Society for the Protection of Animals Abroad, there are no established groups actively working in Iraq to rescue small animals. Veterinarians have been targeted by insurgents and fled the nation in droves.

‘‘This has left a huge black hole for all animals in Iraq,’’ said Dr. Ghazi Mustafa, the group’s director in Jordan.

The State Department, through its provincial reconstruction teams, is working on livestock care, providing free vaccinations and funneling in as many military veterinarians as possible.

But about the only time smaller animals see a vet is to be put down.

Thousands of stray cats and dogs in Baghdad’s Green Zone and on U.S. military installations across Iraq have been trapped and euthanized for health reasons under a program carried out for the military by the contractor KBR Inc., a former Halliburton subsidiary.

‘‘No one involved in the animal control program enjoys the task,’’ said Lt. Col. Raymond F. Dunton, chief of preventive medicine for the military in Iraq. ‘‘Unfortunately, it is critical that we continue this work to protect the health and safety of our service members.’’

Stray dogs and cats, Dunton said, can spread rabies and other diseases that could be transmitted to soldiers.

Last year, nearly 7,100 animals were caught in humane traps by KBR workers, Dunton said. Of those, about 5,300 were euthanized.

At least four of those were cats that Dennis Quine said he had been planning to take back to his native England.

Quine, a former contract maintenance worker for the British Embassy in Baghdad, befriended five feral cats last August. When he returned from a vacation in December, he learned that his cats had been caught by KBR workers.

Quine spent several evenings searching for the cats. Finally, after about a week, the lone survivor — Missy — turned up. Quine knew he had to get her out of Iraq.

He had heard of Louise by word of mouth.

After leaving Iraq in December on a Royal Air Force flight — which did not allow pets — Quine returned on a commercial flight to be reunited with Missy, who had been under Louise’s care. Quine and Missy then made their way to England, where the cat is now in quarantine.

‘‘Friends have said it is stupid, asked why I’m doing this,’’ he said. ‘‘I tell them, ’Hold on, this is nothing less than what I’d do for a friend.’ I was prepared to risk my life to get my cat out.’’

For weeks, Louise had sworn she could no longer take any more pets back to her family home in England and would only act as matchmaker for strays and new owners. ‘‘I’ve got five cats, two dogs, four guinea pigs, some fish and two parents at home,’’ she said.

But as she left Baghdad for a vacation this month, there beside her sat Tigger, a skinny street cat with half a tail, on his way to Britain.

First, a roadside bomb nearly wiped out the taxi heading to the border with Kuwait. The next step was to hide under tarps in the back of a truck. More hardship awaited: six months caged by authorities in England.

But freedom eventually came for Simba, who walked away from captivity with tail held high.

So began the improbable work of the self-proclaimed Cat Lady of Baghdad.

‘‘Some people buy flash cars, others flash clothes. But it’s my animals that float my boat,’’ said Louise, a security consultant in Baghdad who moonlights as a one-woman animal rescue unit that may be the only such organized effort under way in Iraq.

Since Simba’s journey three years ago, she has managed to send four more cats and two dogs back to her native England. The costs — which can run up to $3,500 per animal — are covered by donations and her ‘‘old stuff’’ sold on eBay.

‘‘Collectibles, Cabbage Patch Kids, toys, the lot,’’ said Louise, who asked that only her first name be published because of security worries.

Louise — a tall, blond and blunt-speaking former soldier with an accent as thick as Yorkshire pudding — also has private battles to wage with Iraqi bureaucracy. Completing mountains of paperwork, calls to countless officials and, on one occasion, bursting into tears at the airport have all been required to get animals out of the war zone.

By law, any animal imported to Britain must go through a six-month quarantine. There are also required vaccinations.

It all started when Simba, a white cat with ‘‘tabby bits,’’ strolled onto a U.S. military base. Soon came the planning for Operation Puss ’n’ Boots — as the Simba journey was dubbed by Louise’s colleagues when she worked at the Army outpost near Tikrit, about 80 miles north of Baghdad.

An Iraqi working with Louise was heading to Basra in southern Iraq. She asked if he could take Simba to the border with Kuwait, where an English friend would be waiting.

Just south of Baghdad, a car bomb exploded a few yards from the cab, but no one was hurt. At the border, Simba crossed into Kuwait with the cat hidden.

There may even be a bit of aristocracy among the felines she has rescued.

A popular urban myth in the Green Zone is that the area is overrun with cats because Saddam Hussein kept hundreds in and around his former presidential palace, which now houses the U.S. Embassy.

‘‘Two of my cats — Googles and George — have Ocicat markings,’’ Louise said, referring to a highly prized spotted breed that originated by interbreeding Abyssinian, Siamese and American Shorthair cats. The theory goes that few in Iraq, other than Saddam, would have had such a cat.

It is impossible to gauge how many dogs, cats and other animals have been rescued in Iraq in the past five years by soldiers and foreigners.

In March, Marine Maj. Brian Dennis, was reunited with Nubs after his family and friends raised the costs to fly the 2-year-old mutt from Iraq to San Diego. Dennis found the hound stabbed with a screwdriver in Iraq’s Anbar province and nursed him back to health. He named him Nubs after learning someone cut the ears off believing it would make the dog more aggressive and alert.

Many Western companies also have one or more pets living in their compounds, and cats and dogs are often seen on military bases.

It can be a strong dose of culture shock for many Iraqis who are unaccustomed to having pets and who especially — following widely held Muslim tradition — eschew dogs as unclean.

In January, Iraqi security guards and maintenance workers watched with bemusement as Zeus — one of the dogs Louise rescued — was lavished with belly scratches and other doggy treats by Westerners before it was flown to England.

But when Iraqi workers came near, Zeus would bark savagely and nip at their heels. Louise denied that the pooch had something against Iraqis.

‘‘He just senses their fear, that’s all,’’ she said.

According to an official with the Jordan office of the London-based Society for the Protection of Animals Abroad, there are no established groups actively working in Iraq to rescue small animals. Veterinarians have been targeted by insurgents and fled the nation in droves.

‘‘This has left a huge black hole for all animals in Iraq,’’ said Dr. Ghazi Mustafa, the group’s director in Jordan.

The State Department, through its provincial reconstruction teams, is working on livestock care, providing free vaccinations and funneling in as many military veterinarians as possible.

But about the only time smaller animals see a vet is to be put down.

Thousands of stray cats and dogs in Baghdad’s Green Zone and on U.S. military installations across Iraq have been trapped and euthanized for health reasons under a program carried out for the military by the contractor KBR Inc., a former Halliburton subsidiary.

‘‘No one involved in the animal control program enjoys the task,’’ said Lt. Col. Raymond F. Dunton, chief of preventive medicine for the military in Iraq. ‘‘Unfortunately, it is critical that we continue this work to protect the health and safety of our service members.’’

Stray dogs and cats, Dunton said, can spread rabies and other diseases that could be transmitted to soldiers.

Last year, nearly 7,100 animals were caught in humane traps by KBR workers, Dunton said. Of those, about 5,300 were euthanized.

At least four of those were cats that Dennis Quine said he had been planning to take back to his native England.

Quine, a former contract maintenance worker for the British Embassy in Baghdad, befriended five feral cats last August. When he returned from a vacation in December, he learned that his cats had been caught by KBR workers.

Quine spent several evenings searching for the cats. Finally, after about a week, the lone survivor — Missy — turned up. Quine knew he had to get her out of Iraq.

He had heard of Louise by word of mouth.

After leaving Iraq in December on a Royal Air Force flight — which did not allow pets — Quine returned on a commercial flight to be reunited with Missy, who had been under Louise’s care. Quine and Missy then made their way to England, where the cat is now in quarantine.

‘‘Friends have said it is stupid, asked why I’m doing this,’’ he said. ‘‘I tell them, ’Hold on, this is nothing less than what I’d do for a friend.’ I was prepared to risk my life to get my cat out.’’

For weeks, Louise had sworn she could no longer take any more pets back to her family home in England and would only act as matchmaker for strays and new owners. ‘‘I’ve got five cats, two dogs, four guinea pigs, some fish and two parents at home,’’ she said.

But as she left Baghdad for a vacation this month, there beside her sat Tigger, a skinny street cat with half a tail, on his way to Britain.