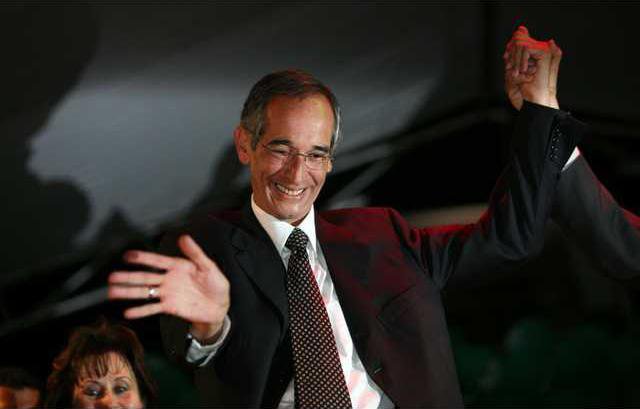

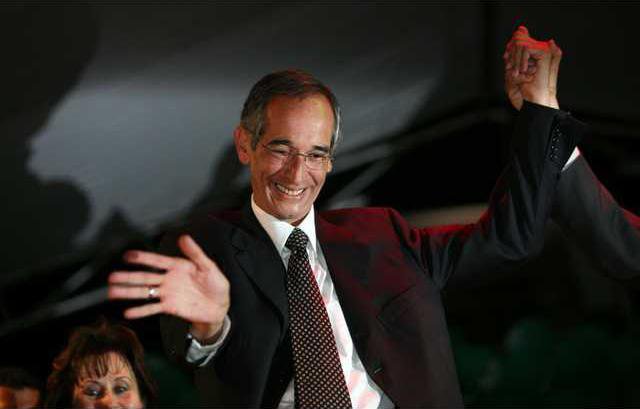

GUATEMALA CITY — Guatemala’s new president, Alvaro Colom received training as a Mayan priest. His vice president is a heart surgeon.

As the two men prepare to take office on Monday, Guatemalans are hoping for some healing.

After a 36-year civil war, and still plagued by poverty, corruption and street gangs, ‘‘Guatemala is sick, very sick, in intensive care,’’ says Vice President Rafael Espada, who gave up a decades-long medical career in Texas to return to Guatemala last year as Colom’s running mate.

‘‘But I think that if we use a smart methodology and do things well, it will be better in four years and in very good shape in 20,’’ he told The Associated Press in an interview.

Guatemalans survive on less than $1 a day, on average. Mayan Indians, half the population of 13 million, suffer discrimination and economic exclusion in a country dominated by those of European ancestry. Colom and Espada are part of that elite, and are promising to move the country leftward, raise taxes, protect human rights and widen access to health care, education and housing.

They face a powerful business class as well as an archaic legal system that makes reforms virtually impossible without constitutional amendments. It ‘‘is a straitjacket for any president,’’ says political analyst Gustavo Porras. ‘‘Any change will take years.’’

Colom is best known for his work with the Guatemalan government and the U.N. to bring home more than 40,000 refugees, mostly Mayan, after the civil war ended in 1996 and invest hundreds of millions of government dollars in the areas that were hardest hit by the war. The refugees honored him by training him as a minister in their religion.

‘‘He was the person that spurred the return of the refugees ... by buying land and giving loans for productive projects between 1992 and 1997,’’ said Gunther Mussig, who led the U.N.-sponsored organization that oversaw the repatriation.

With the departure of President Oscar Berger’s pro-business government, 47 percent of Guatemalans believe the country will be better off, about 29 percent think it will stay the same and 17 percent expect life to be worse, according to a poll published in the El Periodico newspaper. The survey polled 1,008 Guatemalans in December and had a margin of error of 3 percentage points.

Four years ago, when Berger took office, only 39 percent of Guatemalans polled in the same newspaper expected the country to be better managed, while 21 percent thought things would get worse.

Colom ‘‘has been in poor communities and he has a better understanding of the country’s situation,’’ said Mario Rodriguez, who works as a bodyguard. ‘‘I am not expecting great things, because the rich control the country. But let’s hope something changes.’’

Colom and Espada vow to focus their first 100 days on three key areas: public safety, rural aid, and building more schools and public health facilities.

Max Rustrian, a janitor at a public swimming pool, says he’s willing to wait a year, ‘‘because 100 days is not enough to do anything.’’

Pacifying a country overrun by gangs and corruption will be the biggest challenge.

Past crackdowns have failed, leaving gangs to run neighborhoods, behead enemies and extort money from the population.

‘‘I’m sure we can create a more conciliatory nation,’’ Colom, 56, told the AP. ‘‘We know the country’s problems inside and out.’’ Peacemaking, he says, ‘‘taught me to have patience, that things don’t happen in 24 hours.’’

Few Guatemalan families escaped unscathed from the war, which left 200,000 dead and another 40,000 disappeared. Colom’s was no exception — his uncle Manuel Colom, the leftist mayor of Guatemala City, was assassinated by the army in 1979.

He first ran for president as candidate of a guerrilla movement that had laid down its arms and become a political party. He lost a second presidential bid as a center-left candidate. In July, he teamed up with Espada, who left his post as head of heart surgery at Houston’s Methodist Hospital and returned to Guatemala to run for the vice presidency.

Espada, who turns 64 on inauguration day, often performed free surgery on needy patients during visits to Guatemala. He brings something of his operating-room experience to his new job, saying: ‘‘A surgeon is disciplined, studious, responsible and, above all, a person capable of making life-and-death decisions every day.’’

As the two men prepare to take office on Monday, Guatemalans are hoping for some healing.

After a 36-year civil war, and still plagued by poverty, corruption and street gangs, ‘‘Guatemala is sick, very sick, in intensive care,’’ says Vice President Rafael Espada, who gave up a decades-long medical career in Texas to return to Guatemala last year as Colom’s running mate.

‘‘But I think that if we use a smart methodology and do things well, it will be better in four years and in very good shape in 20,’’ he told The Associated Press in an interview.

Guatemalans survive on less than $1 a day, on average. Mayan Indians, half the population of 13 million, suffer discrimination and economic exclusion in a country dominated by those of European ancestry. Colom and Espada are part of that elite, and are promising to move the country leftward, raise taxes, protect human rights and widen access to health care, education and housing.

They face a powerful business class as well as an archaic legal system that makes reforms virtually impossible without constitutional amendments. It ‘‘is a straitjacket for any president,’’ says political analyst Gustavo Porras. ‘‘Any change will take years.’’

Colom is best known for his work with the Guatemalan government and the U.N. to bring home more than 40,000 refugees, mostly Mayan, after the civil war ended in 1996 and invest hundreds of millions of government dollars in the areas that were hardest hit by the war. The refugees honored him by training him as a minister in their religion.

‘‘He was the person that spurred the return of the refugees ... by buying land and giving loans for productive projects between 1992 and 1997,’’ said Gunther Mussig, who led the U.N.-sponsored organization that oversaw the repatriation.

With the departure of President Oscar Berger’s pro-business government, 47 percent of Guatemalans believe the country will be better off, about 29 percent think it will stay the same and 17 percent expect life to be worse, according to a poll published in the El Periodico newspaper. The survey polled 1,008 Guatemalans in December and had a margin of error of 3 percentage points.

Four years ago, when Berger took office, only 39 percent of Guatemalans polled in the same newspaper expected the country to be better managed, while 21 percent thought things would get worse.

Colom ‘‘has been in poor communities and he has a better understanding of the country’s situation,’’ said Mario Rodriguez, who works as a bodyguard. ‘‘I am not expecting great things, because the rich control the country. But let’s hope something changes.’’

Colom and Espada vow to focus their first 100 days on three key areas: public safety, rural aid, and building more schools and public health facilities.

Max Rustrian, a janitor at a public swimming pool, says he’s willing to wait a year, ‘‘because 100 days is not enough to do anything.’’

Pacifying a country overrun by gangs and corruption will be the biggest challenge.

Past crackdowns have failed, leaving gangs to run neighborhoods, behead enemies and extort money from the population.

‘‘I’m sure we can create a more conciliatory nation,’’ Colom, 56, told the AP. ‘‘We know the country’s problems inside and out.’’ Peacemaking, he says, ‘‘taught me to have patience, that things don’t happen in 24 hours.’’

Few Guatemalan families escaped unscathed from the war, which left 200,000 dead and another 40,000 disappeared. Colom’s was no exception — his uncle Manuel Colom, the leftist mayor of Guatemala City, was assassinated by the army in 1979.

He first ran for president as candidate of a guerrilla movement that had laid down its arms and become a political party. He lost a second presidential bid as a center-left candidate. In July, he teamed up with Espada, who left his post as head of heart surgery at Houston’s Methodist Hospital and returned to Guatemala to run for the vice presidency.

Espada, who turns 64 on inauguration day, often performed free surgery on needy patients during visits to Guatemala. He brings something of his operating-room experience to his new job, saying: ‘‘A surgeon is disciplined, studious, responsible and, above all, a person capable of making life-and-death decisions every day.’’