GUANTANAMO BAY NAVAL BASE, Cuba — The accused mastermind of the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks said he welcomed martyrdom at U.S. hands, as he and four codefendants faced trial for war crimes without the benefit of lawyers.

Thursday’s arraignment at this isolated U.S. Navy base marked the first time that Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the former No. 3 leader of al-Qaida, has been seen since he was captured in Pakistan in 2003.

Judge Ralph Kohlmann said he would set a trial schedule later.

Mohammed said he would welcome being executed after the judge warned him he faces the death penalty if convicted of organizing the attacks on America.

‘‘Yes, this is what I wish, to be a martyr for a long time,’’ Mohammed said. ‘‘I will, God willing, have this, by you.’’

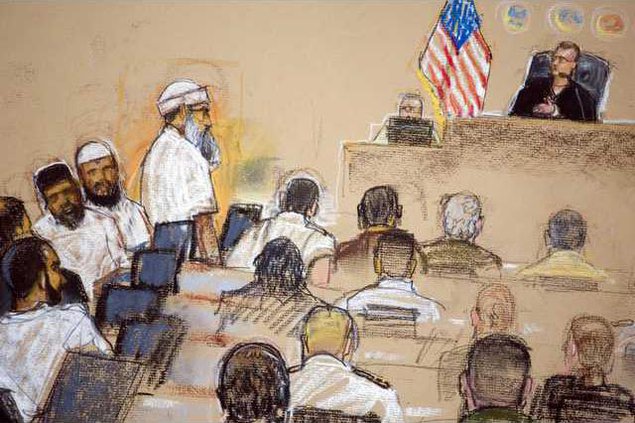

Mohammed wore dark-framed prison-issue glasses, a turban and a bushy, gray beard and was noticeably thinner. It was a stark change from the slovenly man with disheveled hair, unshaven face and T-shirt seen in the widely distributed photograph after his capture in Pakistan. He looked older than his 45 years.

One of the civilian attorneys he spurned, David Nevin, later told The Associated Press that he would attempt to meet with Mohammed to ‘‘hear him out and see if we can give him information that is helpful.’’

Asked how any attorney could defend a man who wants the death penalty, the Boise, Idaho, lawyer said: ‘‘It’s a tricky matter. I don’t have a good answer for you.’’

Waleed bin Attash, who allegedly selected and trained some of the hijackers, asked the judge whether the Sept. 11 defendants — who all face possible death sentences — would be buried at Guantanamo or if their bodies would be shipped home if they were executed.

Kohlmann, a Marine colonel with a crewcut who was dressed in black robes, refused to address the question.

The five co-defendants were at turns cordial and defiant at their arraignment, the first U.S. attempt to try in court those believed to be directly responsible for killing 2,973 people in the bloodiest terrorist attack ever on U.S. soil. All five said they would represent themselves.

But defense attorneys said four men intimidated a fifth defendant to join them in declaring they didn’t want attorneys.

At a news conference, the military defense attorneys denounced the court for allowing the defendants to talk among themselves before and during their joint arraignment, saying this is when Mustafa Ahmad al-Hawsawi was pressured into going without a lawyer.

‘‘It was clear Mr. Mohammed was trying to intimidate Mr. Hawsawi,’’ said Army Maj. Jon Jackson, his lead military attorney. ‘‘He was shaking.’’

Chief military defense counsel Stephen David, an Army colonel, said the fact that the alleged coconspirators were allowed to talk unhindered in the courtroom in their first meeting since they were captured years ago was troubling.

‘‘We will have to investigate,’’ David said.

The other defendants appeared to be in robust health but al-Hawsawi, who allegedly helped the Sept. 11 hijackers with money and Western-style clothing, looked thin and frail and sat on a pillow on his chair.

Army Col. Lawrence Morris, the chief prosecutor at the military trials here, said his office was not responsible for controlling when defendants talk to each other, but said they should not be pressured into renouncing their lawyers.

‘‘The government is as concerned as the defense on the integrity over counsel relationships,’’ he said.

The war-crimes tribunal is the highest-profile test yet of the military’s tribunal system, which faces an uncertain future. The tribunals have faced repeated legal setbacks, including a Supreme Court appeal on the rights of Guantanamo detainees that could produce a ruling this month halting the proceedings.

The arraignment, in which no pleas were entered, indicated that hatred for the United States among some of the defendants remains at a boil.

The other defendants are Ali Abd al-Aziz Ali, known as Ammar al-Baluchi, a nephew and lieutenant of Mohammed; and Waleed bin Attash, who allegedly selected and trained some of the hijackers.

Thursday’s arraignment at this isolated U.S. Navy base marked the first time that Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the former No. 3 leader of al-Qaida, has been seen since he was captured in Pakistan in 2003.

Judge Ralph Kohlmann said he would set a trial schedule later.

Mohammed said he would welcome being executed after the judge warned him he faces the death penalty if convicted of organizing the attacks on America.

‘‘Yes, this is what I wish, to be a martyr for a long time,’’ Mohammed said. ‘‘I will, God willing, have this, by you.’’

Mohammed wore dark-framed prison-issue glasses, a turban and a bushy, gray beard and was noticeably thinner. It was a stark change from the slovenly man with disheveled hair, unshaven face and T-shirt seen in the widely distributed photograph after his capture in Pakistan. He looked older than his 45 years.

One of the civilian attorneys he spurned, David Nevin, later told The Associated Press that he would attempt to meet with Mohammed to ‘‘hear him out and see if we can give him information that is helpful.’’

Asked how any attorney could defend a man who wants the death penalty, the Boise, Idaho, lawyer said: ‘‘It’s a tricky matter. I don’t have a good answer for you.’’

Waleed bin Attash, who allegedly selected and trained some of the hijackers, asked the judge whether the Sept. 11 defendants — who all face possible death sentences — would be buried at Guantanamo or if their bodies would be shipped home if they were executed.

Kohlmann, a Marine colonel with a crewcut who was dressed in black robes, refused to address the question.

The five co-defendants were at turns cordial and defiant at their arraignment, the first U.S. attempt to try in court those believed to be directly responsible for killing 2,973 people in the bloodiest terrorist attack ever on U.S. soil. All five said they would represent themselves.

But defense attorneys said four men intimidated a fifth defendant to join them in declaring they didn’t want attorneys.

At a news conference, the military defense attorneys denounced the court for allowing the defendants to talk among themselves before and during their joint arraignment, saying this is when Mustafa Ahmad al-Hawsawi was pressured into going without a lawyer.

‘‘It was clear Mr. Mohammed was trying to intimidate Mr. Hawsawi,’’ said Army Maj. Jon Jackson, his lead military attorney. ‘‘He was shaking.’’

Chief military defense counsel Stephen David, an Army colonel, said the fact that the alleged coconspirators were allowed to talk unhindered in the courtroom in their first meeting since they were captured years ago was troubling.

‘‘We will have to investigate,’’ David said.

The other defendants appeared to be in robust health but al-Hawsawi, who allegedly helped the Sept. 11 hijackers with money and Western-style clothing, looked thin and frail and sat on a pillow on his chair.

Army Col. Lawrence Morris, the chief prosecutor at the military trials here, said his office was not responsible for controlling when defendants talk to each other, but said they should not be pressured into renouncing their lawyers.

‘‘The government is as concerned as the defense on the integrity over counsel relationships,’’ he said.

The war-crimes tribunal is the highest-profile test yet of the military’s tribunal system, which faces an uncertain future. The tribunals have faced repeated legal setbacks, including a Supreme Court appeal on the rights of Guantanamo detainees that could produce a ruling this month halting the proceedings.

The arraignment, in which no pleas were entered, indicated that hatred for the United States among some of the defendants remains at a boil.

The other defendants are Ali Abd al-Aziz Ali, known as Ammar al-Baluchi, a nephew and lieutenant of Mohammed; and Waleed bin Attash, who allegedly selected and trained some of the hijackers.