NAIROBI, Kenya — As Kenyans die by the hundreds in gritty city slums and rolling cornfields in the countryside, their fate rests with two men who appear more intent on the struggle for power than on the turmoil it has set off.

One is a 74-year-old political veteran, Mwai Kibaki, a London-trained economist who has been part of every Kenyan government since the East African nation’s independence from Britain in 1963.

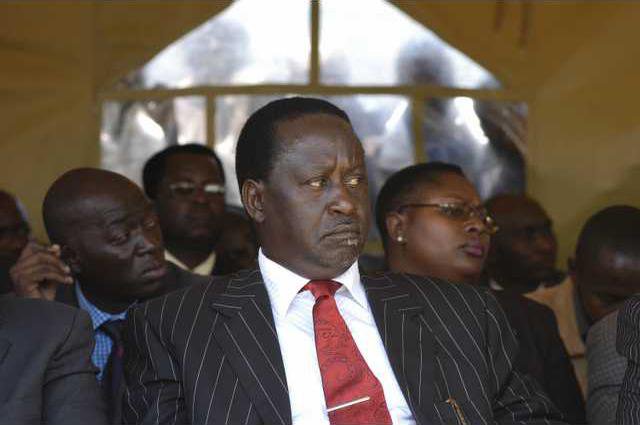

The other is Raila Odinga, born into politics 45 years ago when his father was fighting for Kenya’s independence. An engineer trained in the former East Germany, Odinga has had a long and adversarial relationship with Kenya’s governments, including serving six years in detention for alleged treason in a 1982 coup attempt.

Kibaki, declared winner of Dec. 27 elections in a vote tally that international and local observers said was rigged, is determined to remain president, playing out an old story on a continent where few surrender power graciously.

Odinga, a lawmaker and factory owner whose father was Kenya’s first vice president, first ran for president in 1997. He served as a Cabinet minister in Kibaki’s administration for two years before being booted out in 2005 for fighting a draft constitution that would make Kibaki more powerful.

As former U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan arrived Wednesday to lead flagging international mediation efforts, neither man appeared ready to compromise.

‘‘Let’s face it. Our leaders don’t care how many people are felled by police bullets, hacked to death or burnt alive,’’ Macharia Gaitho, managing editor of the country’s leading Nation Media Group, wrote in an editorial.

In his nightmares, Gaitho writes, he sees Kibaki ‘‘balancing precariously on a gold and diamond-bedecked throne that is threatening to topple over because it is standing unsteadily on a mountain of decapitated human bodies.’’

Odinga appears ‘‘climbing over the bodies, knee-deep in blood, with his arm outstretched to grab the throne.’’

Both men blame each other for the bloodshed.

Annan did score a small victory Wednesday, persuading Odinga to call off protests that had been planned for Thursday in defiance of a government ban. Scores of Odinga’s supporters were gunned down by riot police during earlier demonstrations.

In rural western Kenya, Odinga’s supporters have been hunting down people of Kibaki’s Kikuyu tribe.

The official toll stands at 685 dead, but it is probably much higher.

Kibaki has ignored opposition calls that he acknowledge the vote count was suspect, and may be encouraged to see the number of protesters dwindling from the tens of thousands who turned out in the week after he was declared the winner by the smallest margin in Kenya’s history.

Those left to confront police bullets are mainly angry young men from the sprawling slums that house 65 percent of the capital’s population, a marginalized majority in a country where pervasive corruption enriches the elite few.

As the protests lost steam, Odinga called for an economic boycott this week of businesses owned by what’s called the Mount Kenya Mafia, the tight circle of privileged Kikuyu businessmen whose long dominance of politics and the economy has created deep-seated resentment.

The government said the boycott call was ‘‘economic sabotage,’’ though it has had little visible effect. Targeted businesses include public transport company CitiHoppa, whose buses are driving around Nairobi as overcrowded as ever.

In one telling incident, a man from Odinga’s Luo tribe boarded a bus and was ordered by the Kikuyu driver to pay more than the usual fare because ‘‘it’s your people’’ causing the trouble. The man protested, and passengers of several tribes were drawn into a rowdy debate. They sided with the Luo passenger, who was allowed to ride for the normal fare.

But the economy, heavily dependent on tourism, already has suffered — thousands of tourists have canceled vacations.

As the economy reels and Kenyans increasingly call for peace, Kibaki and Odinga both are ringed by hard-liners. In a country of patronage politics, businessmen and civil servants depend on their man being in power.

Annan, a Ghanaian, has a tough job.

As editor Githai wrote: ‘‘We have one stubborn old man determined to hang on to the presidency whatever it takes in blood ... We have an ambitious and equally stubborn younger man who feels strongly that he was rightfully elected president and will likewise do whatever the cost in blood.’’

——

Michelle Faul is chief of Africa news for The Associated Press.

One is a 74-year-old political veteran, Mwai Kibaki, a London-trained economist who has been part of every Kenyan government since the East African nation’s independence from Britain in 1963.

The other is Raila Odinga, born into politics 45 years ago when his father was fighting for Kenya’s independence. An engineer trained in the former East Germany, Odinga has had a long and adversarial relationship with Kenya’s governments, including serving six years in detention for alleged treason in a 1982 coup attempt.

Kibaki, declared winner of Dec. 27 elections in a vote tally that international and local observers said was rigged, is determined to remain president, playing out an old story on a continent where few surrender power graciously.

Odinga, a lawmaker and factory owner whose father was Kenya’s first vice president, first ran for president in 1997. He served as a Cabinet minister in Kibaki’s administration for two years before being booted out in 2005 for fighting a draft constitution that would make Kibaki more powerful.

As former U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan arrived Wednesday to lead flagging international mediation efforts, neither man appeared ready to compromise.

‘‘Let’s face it. Our leaders don’t care how many people are felled by police bullets, hacked to death or burnt alive,’’ Macharia Gaitho, managing editor of the country’s leading Nation Media Group, wrote in an editorial.

In his nightmares, Gaitho writes, he sees Kibaki ‘‘balancing precariously on a gold and diamond-bedecked throne that is threatening to topple over because it is standing unsteadily on a mountain of decapitated human bodies.’’

Odinga appears ‘‘climbing over the bodies, knee-deep in blood, with his arm outstretched to grab the throne.’’

Both men blame each other for the bloodshed.

Annan did score a small victory Wednesday, persuading Odinga to call off protests that had been planned for Thursday in defiance of a government ban. Scores of Odinga’s supporters were gunned down by riot police during earlier demonstrations.

In rural western Kenya, Odinga’s supporters have been hunting down people of Kibaki’s Kikuyu tribe.

The official toll stands at 685 dead, but it is probably much higher.

Kibaki has ignored opposition calls that he acknowledge the vote count was suspect, and may be encouraged to see the number of protesters dwindling from the tens of thousands who turned out in the week after he was declared the winner by the smallest margin in Kenya’s history.

Those left to confront police bullets are mainly angry young men from the sprawling slums that house 65 percent of the capital’s population, a marginalized majority in a country where pervasive corruption enriches the elite few.

As the protests lost steam, Odinga called for an economic boycott this week of businesses owned by what’s called the Mount Kenya Mafia, the tight circle of privileged Kikuyu businessmen whose long dominance of politics and the economy has created deep-seated resentment.

The government said the boycott call was ‘‘economic sabotage,’’ though it has had little visible effect. Targeted businesses include public transport company CitiHoppa, whose buses are driving around Nairobi as overcrowded as ever.

In one telling incident, a man from Odinga’s Luo tribe boarded a bus and was ordered by the Kikuyu driver to pay more than the usual fare because ‘‘it’s your people’’ causing the trouble. The man protested, and passengers of several tribes were drawn into a rowdy debate. They sided with the Luo passenger, who was allowed to ride for the normal fare.

But the economy, heavily dependent on tourism, already has suffered — thousands of tourists have canceled vacations.

As the economy reels and Kenyans increasingly call for peace, Kibaki and Odinga both are ringed by hard-liners. In a country of patronage politics, businessmen and civil servants depend on their man being in power.

Annan, a Ghanaian, has a tough job.

As editor Githai wrote: ‘‘We have one stubborn old man determined to hang on to the presidency whatever it takes in blood ... We have an ambitious and equally stubborn younger man who feels strongly that he was rightfully elected president and will likewise do whatever the cost in blood.’’

——

Michelle Faul is chief of Africa news for The Associated Press.